Art as Therapy

Gross

July 18, 2014

“It appears your fine motor skills on your right side and your gross motor skills on your left have been affected,” he informed me after assuring me the CT Scan didn’t reveal hemorrhaging in the brain. “Spend this week painting and reading, and we will reevaluate one week at a time. Oh, and do simple math. Nothing much. Balancing your check book, things like that.”

I didn’t wish to inform him I NEVER balanced my checkbook, but I realized laying out the unfinished canvas project from last year’s cross-country bike trip would be the perfect mathematical challenge. “Time to tackle it,” I silently resigned myself.

As I had attempted to walk across his office, heel to toe in roadside sobriety test fashion, my left foot dragged perceptibly, and I stumbled. I knew his insistence upon my not driving my new Fiat was a necessary evil, and I also understood it may be awhile before I could safely return to the airport.

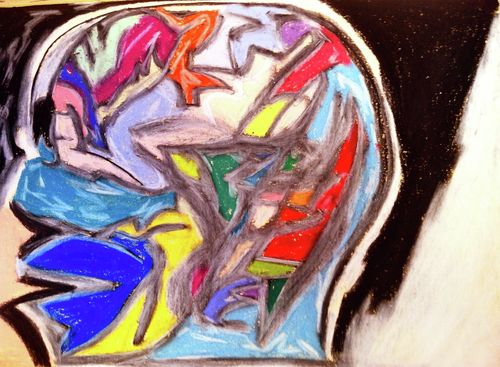

Art as therapy. Writing, painting and doodling have always been exactly that: my way of expressing myself when I couldn’t seem to find voice to my thoughts, emotions and desires.

As an insomniac, the endless hours of sleep have been refreshing. Not the nightmare-infused sleep I normally avoid, but the dead, thoughtless sleep of illness—and lots of it.

“I don’t want you taking more than two naps per day,” he added, stating that I would also have to somehow awaken myself in the middle of the night.

“That’s what my girl does best,” I laughed, assuring him that she disturbs me at least once throughout the night with her panting insistence on a fresh bowl of water. Oddly, though, I managed to even sleep through that, as well as the restless pacing she usually does about the same time my internal clock goes off somewhere before the next nightmare begins.

As I clutched the paintbrush in my hand that had been strengthened by the heavy bags I wield at the airport, my forearm began to ache. I had covered about 1/3 of my 11 X 6’ spread of canvases, a feat that should have been easy. It wasn’t that my muscles weren’t in top condition; my fine motor skills, those the doctor had noted were less responsive, were well, exactly that: unresponsive.

The first few lines I drew on the sheet of paper representing the canvases that lay strewn across the garage were excruciatingly painful, predicting the frustration I would have as I struggled to distinguish the ½ inch from the 1 inch marks on the ruler, foreshadowing the annoying ache I felt on the left side of my brain as I established what would serve as the ground-line for the series. The result: a confusing mass of scribbles intersected by sharp grey lines.

Years of technique gone in a single moment of carelessness by my coworker who had lowered the belt loader onto my head as I reached for the fallen bag. The diagnosis: mild concussion. Somehow seems an empty one when compared with other diagnoses I have heard some of my friends report: cancer; inoperable brain tumor; unidentified infection; debilitating muscle spasms. Only traumatic brain injury.

No, I am not angry with him. I understand it is an opportunity to relearn old skills, perhaps this time without the poor habits that had infused my work in the past.

Each incident, each lesson in life becomes a new step toward further exploration of self as well as appreciation for others who have undergone a challenge, those who successfully emerge victorious on the other side. No, not necessarily cured. Just determined to strive toward becoming a more fulfilled, more sympathetic person. Those who have experienced their own “trial by fire.”

“I love you,” I wrote to my best friend, who had shifted her emphasis from dancer to phenomenological theorist after sustaining an injury that may have ended her career as performer.

I glance back at my sketch, pick up the stick of chalky pastel, and start again.

One foot in front of the other, just as it was last year. Just as it always is. But this time, rather than being a physical struggle, it is mental resolve to regain that which has been lost.

“Perhaps this will be known as your fuzzy period,” he joked. Lines blurred between imagination, reality and injury: past, present and future. Isn’t that what the essence of life is all about?

Fuzzy

July 24, 2014

“Do you remember when the photo was taken?” I asked him.

Since my injury, he has reached out on a number of occasions. Friends and family both have rallied, offering not just well wishes, but also by challenging me and stimulating me, encouraging me to remember.

After he answered, I provided as many details as possible, exercising my memory, recounting specific moments before and after the picture had been snapped.

“Details. They are the essence of an effective personal narrative,” I instructed my incoming freshman students the first week of their college English Composition class.

It isn’t without coincidence that a beginning writer’s first assignment comprises personal narrative. Stories of ourselves and our own experiences shape who we are and who we will become. Nothing is more frightening than facing the potential loss of those stories.

I’ve encountered both physical and emotional setbacks, rebuilding my physical stamina following a torn ACL that left me in a wheelchair for a few months to debilitating moments in which I had been diagnosed as pre-verbal because of emotional meltdowns. Yet I’ve never faced the possibility of being unable to reason, unable to recall events, even if these cognitive processes manifest themself internally. I always had an internal dialogue, a private, logical sequence of thoughts by which I was able to fight my way back into who I perceived myself as being, a process I now struggle to possess.

The nausea associated with movement has begun to fade, but the ache that comes with cogent thought remains. As an insomniac relishing the ability to sleep, I am now instructed to use my mind rather than sleep too often.

And the new car, the first vehicle I have owned in four years, sits idly on the road per doctor’s mandated “no driving.” Irony at its best.

“Have you noted any changes in smell?” he asked during our last appointment.

“No, but the first glass of orange juice I had following the concussion was the best I have ever had!” I exclaimed, adding, “I also feel pain more intensely. Those aches that come with aging seem to be far more acute than they were a week ago.”

“Odd, isn’t it, how the brain controls everything we perceive, everything we feel?” he noted.

“You move slowly,” my son observed over dinner. He and I hadn’t seen one another for a few months, his easy criticism typical of the candid conversations we have always shared with one another. Sometimes it takes distance from an object to allow for critical assessment, and he had been quick to note the difference in my speech and measured, deliberate gait.

“Chris was right,” my daughter noted as she watched me hurdle over the gate, a shortcut we almost always take to avoid wrangling the escaped girls back into the fence that both of them could easily clear themselves. The young, agile Min-Pin peeked over the closed gate, balancing on her muscular haunches while my big old girl effortlessly peered over the top, barking behind us.

We had all noted their compliance to stay within their own boundaries on a number of occasions, particularly recently when the only thing confining them into their familiar space was a wobbly, poorly erected wire enclosure.

A neighbor, angry with her husband, had recently plowed into the permanent fence, tearing out several feet in the process, snapping the plastic uprights as effectively as she had ripped apart her bumper and steering column.

A few days after the crash, tired of taking the girls on a leash as they took care of business, my niece and I late one night constructed a makeshift barricade using the light of our cell phones and a small rock as our only tools. The girls’ own body weight and energy could easily have uprooted the temporary barrier constraining them. The enclosure is held precariously upright by a few hastily buried posts.

On several occasions, we have all stood outside of the fence—both the permanent and the more recently, rapidly constructed replacement—enticing the girls to see if their determination to join us would lead to their flight. No amount of inducement elicited said response, so we rest assured that they are comfortable enough within their secure space to remain in their own yard.

“Did you know the gate was open?” my niece asked as I emerged from the house yesterday. I had spent the day working in the yard with little to show for my slow, measured movement. The gate had been secure as far as I knew. She added, “Apparently they stepped out to visit with a passing neighbor then came back into the yard.”

Devotion and loyalty at its best. Or worst.

How often do we ourselves imitate their behavior, allowing ourselves to be confined within a specific emotional, physical or mental space, resting contentedly within a particularly comfortable place? As feeling, reasoning, sentient beings it is the moments in which familiar barricades fall that allow us to look beyond the parameters which too often we have ourselves erected to keep us from reaching beyond our own perceived boundaries.

Do the details of our personal narrative confine, serving as tools wherewith we construct our own limitations? Or do we push beyond the borders of self- perception toward our own re-creation?

I pat each one of the girls on their heads and call them in for their nightly “snick,” swallow down my medication with a glass of orange juice to quell the pain and head to bed.

“One Step at a Time”

July 26, 2014

“I want you to start physical therapy,” he casually threw over his shoulder while typing out the summary of our last visit.

It was the third time I had failed what I have come to identify as the concussive roadside test.

“Place one foot in front of the other, heel to toe,” he instructed me, as he stood beside me with his hands in a guarded position, ready to catch me should I stumble. “Take it slowly, one step at a time.”

The right foot responds well, but the left foot hesitates to do what once came so naturally. And the moment I feel his bracing, cautious hands on my arm, I am faced with the realization that I have failed.

Although he had mentioned physical therapy as a possibility with the first appointment, I hadn’t really given it much thought. Then again, the pain was so excruciating, I wasn’t giving anything thought too much at all.

His offhand referral jolted me: physical therapy meant I was broken and needed fixed. At least the inner dialogue has returned, but I don’t usually like what the voice is telling me.

“Apparently you’re not as hard headed as we thought,” my ex jokingly texted me after learning of the next step toward recovery.

“It took an hydraulic lift to prove otherwise,” I playfully retorted, never adding, “But what about my ability to think cogently or type without the screen being punctuated by red squiggly lines?”

The unasked question remains unanswered. Although the physical therapists may be able to teach me to walk and move in an “unguarded fashion,” as the doctor had described it, but will I really ever confidently speak without those pauses people have noted? Will I ever be able to type out words without the page being filled with red or green squiggly lines?

“What are you going to do over the next few weeks?” my niece asked after hearing the outcome of my latest appointment.

I pointed behind me at the canvases I had purchased with the gift card she gave me for Christmas. “Finish these,” I replied.

“Headache, dizziness, nausea, loss of memory, irritability, depression, change in personality…” I interrupted her before she could continue reading the list of potential prolonged symptoms.

“I have read them. Perhaps because I am aware of them, I am better prepared to guard against them,” I informed cursorily her, realizing immediately that my tone had been uncharacteristically sharp.

The reminders that I have undergone a change, that I am “broken” appear all too frequently.

Art as therapy? I can barely paint my toenails without having them look like a preschooler applied the polish! And each time I doze, the last things I look at are the unfinished canvases stacked beside me.

“Final question,” the anonymous voice on the other side of the phone asked me as we concluded the recorded workman’s compensation claim. “What are your hobbies?”

“I am an artist,” I responded. “I taught art and English Composition for ten years before taking the job at the airport.”

Silence. Perhaps she noted the defensive sharpness in my voice, masking my frustration.

“Thank you,” she finally responded, adding, “If there is anything else we need, I will let you know.”

“I am jealous of those who do a sketch a day,” an online correspondent, a fellow art teacher noted, attaching a picture of her recent work.

A sketch a day. An easy assignment stepping toward mastery.

Looking Past the Boundaries: Remembering Details While Reshaping the Definitive Self

In-Seine-ity

July 28, 2014

“You asked me a very pointed question a few days ago regarding the European influences that led up to the World Wars. We had a wonderful discussion regarding the Franco-Prussian War and the economic turmoil that prepared Germany for Hitler’s fascism. What was the question?” I meant to ask.

The conversation had included snippets from my favorite lecture discussing the alliance between Russia and France, the period which yielded the overly ornate bridge spanning Paris’ Seine, Pont Alexandre III.

Instead, when I heard the recorded message followed by a high-pitched beep on his answering machine, I went blank, informing him that I had an important question but had immediately forgotten it, adding, “Aren’t you glad you have a sister who is suffering with a concussion?”

My memory is about as disjunctive as my vision, skipping from one point to another, momentarily blurring, then returning to clarity. The same troubling pattern I experience while attempting to speak.

The visual fractures occur with bright light or intensively high-pitched noises, highly problematic while driving or listening to classical music that is punctuated with violin concertos or flute sonatas.

The mental fractures are the ones that remain most troubling.

“You’re going to have to get back on your bike and ride home,” he shouted to me over his shoulder as he rode away from me.

My legs were once again covered with blood, staining my socks red.

I hastily brushed the loose gravel from my wound, not taking the time to brush my tears from my eyes, knowing that the blurred vision that always accompanies tears would dissipate as quickly as the blood would clot in Colorado’s dry air once I started pedaling again.

“Is that ‘Pomp and Circumstance’?” my niece asked one evening shortly after I arrived in Colorado.

She and I had slipped easily into a routine, eating dinner in her aviary with her sun conures sitting on her shoulder, picking finically at her food while our girls eagerly, jealously eyed their freedom from the floor, anxiously awaiting any crumbs they were sure to drop.

“Yes,” I sheepishly replied. “It is one of my favorite pieces. I keep it on my iTunes as a reminder that I actually possess three degrees, hoping that someday I will eventually be able to return to a position as instructor.”

“You’ll be surprised how many of us have degrees,” the former high school history teacher informed me as we stood in the parking lot at the airport.

He had earned his Master’s of Education with a thesis centered on rural education.

Like me, he had spent most of his career teaching. His position had been eliminated when the small K-12 school where he taught lost its budget and had been absorbed into a larger district located 40 miles away.

For his students, it meant awaking before dawn to catch their bus for the long commute.

For him, it meant floating from one job to the next, first taking positions in business, then, like me, eventually landing a blue-collar job because even the recruiters for the businesses dismissed him with the pat answer we have all heard: “You are over-qualified for the position.”

His years serving his rural community not just as educator but as girls volleyball coach meant nothing to the larger school districts, especially since his higher degree and lengthy experience bumped him into a higher wage bracket.

He simply couldn’t compete in the bigger markets against the fresh-faced, eager young graduates emerging from the colleges, degree in hand and willing to take a low salary.

We are victims of our own success to an extent, taking the local children, nurturing them to maturity, showing them that they, too, could leave their low-income situation, earn a college degree and become successful members of society.

Little did we realize we were training those who would eventually supplant us.

“Don’t you think that’s a waste of your degree?” she pompously asked, after I informed her I wished to return to teach at a community college once I left the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

I lowered my eyes, not to hide my shame but to hide my indignation. The inner-dialogue had a quick reply; “What makes you think that the community college students are any less worthy of a well-trained teacher than any other student?” I felt like shouting.

I had learned my lesson, though.

As an older student, I often spoke my mind, but lately I had realized the reason younger students were more likely to be favored was often because they DIDN’T speak their minds.

“That will change soon enough,” I learned to remind myself as quickly as I had learned to lower my eyes rather than shoot off the quick retort.

“Ms. So-and-So would like to cordially invite you to” the stiff, expensively printed commencement announcements once read. Now the invitations are less formal, usually in the form of an FB event created and shared with all my former student’s contacts.

I love the change, and I cherish the fact that I am still in touch with so many of them through social media, a bridge spanning one academic generation to the next.

But the reality remains: with each announcement, I am that much further from finding employment within my field.

Yet another reality remains: my former students’ successes reminds me of my own success as educator.

They serve as reflection of my own triumph. And a foreshadowing of my own failure.

My fingers—stained with shades of grey, blue and yellow from my favorite artists’ soft pastels that are no longer being manufactured—ache from today’s sketch, the art that serves as physical therapy.

“You’re going to have to get back on your bike and ride home…”

My brother’s shouted voice echoes back to me across time.

Filters

October 18, 2014

The autumn warmth seeps through my sweater as soft jazz slips smoothly across the concrete. Long shadows creep alongside the sleek, obscure voice that is nearly lost in the roar of traffic.

The dying cricket slowly chirps, choosing to sing with the smoky jazz rather than repeat the tempo of the speeding cars. He’s had his summer’s fling and no longer frantically calls to his mate, but serenades simply for his own self-satisfaction.

No filters.

Each sound serves its two-fold purpose, capturing my attention and mirroring the self-fulfilling existence of the cricket. Noise for Noise’s Sake.

“Fever…”

The lyrics were once familiar enough to possess meaning.

“Fever when you hold me tight.”

Words, emotions and memories as obscure and purposeless as the cricket’s lackadaisical, self-satisfied chirp.

“You need to purchase a planner, “ she instructed me at the close of our last session. “I use a weekly one with enough space to write a few notes alongside my appointments. You are working your brain too hard trying to remember everything.”

“Dance, dance, dance!”

“What about shopping?” the other therapist asked.

I respond with a far-away glance.

“Your face gives you away,” she notes, making a few hasty scribbles on the blank sheet of paper.

My life, my reactions, my balance, my memories, my words transposed into her own, bright blue, indecipherable blotches on a white page. Rorschach tests representing my identity.

“I may choose a slightly different style of planner than yours,” I tell the cognitive therapist. “Something with a bit more space where I may write or draw.”

“It will be larger and heavier,” she responds, cautioning me she doesn’t want it to overburden me, a subtle reminder that I am to carry it with me everywhere I go.

“I want you to journal daily,” I instructed my Developmental English students. “Purchase something as small or as large as you’d like, but something you will carry with you wherever you go. Words on paper. For now, that’s all that matters, even if all you are able to write for the day is a shopping list.”

“I am a photographer,” I defiantly reply. “I am accustomed to carrying extra weight.”

The sound of an instrument I once could identify dances along with a piano, echoing its slow rhythm while a dog barks from another nearby table.

No filters.

“I can tell by your face you struggle with shopping,” she notes, adding, “Most patients do. Too much to filter.”

I reach for another tissue, ruefully smiling, knowing my tears serve as an answer.

The bike ride along the path motivates me since the prospect of a planner doesn’t. Cool weather, brilliant hues, crunching leaves combining into a sensory poem set to the motion of my tires, an easy autumnal sound contrasting sharply with the dizzying shrillness of the bookstore with conversations shouted through impenetrably high caverns of stacked books.

No filters.

The yellow leaves shimmer in the sunlight, loosely hung upon the branches to which they tightly clung throughout the spring and summer of their short lives. A fallen comrade skirts across the concrete, scratching its claws as the breeze effortlessly carries it toward the path of its destruction into the oncoming, rushing cars.

I leaf through the planners, clinging to the softness of the familiar Moleskin, the legendary patent claiming to be the favored notebooks of Hemingway.

Somewhere in a box left behind in a different chapter of my life is a stack of them. Moleskins, some empty, most possessing hastily scribbled notes from lectures, books and museums, thoughts that are now firmly, inaccessibly locked somewhere in my brain by a single blow.

“The additional space in my larger planner,” I inform her, “will allow me—no, encourage me—too practice my longhand writing skills.” The tears begin to fall again as I recall the pain of re-teaching myself how to make circles.

“Fifteen-month,” “weekly,” “large,” “lined,” the Moleskin planner description boasts. I carry it wearily from the rack, heavy hearted, knowing that even during the last few months of earning my Master’s degree—while conducting my research, writing and rewriting my thesis, attending classes and keeping appointments—the planner I purchased had become extra weight, an unnecessary item lost in a zipped pocket of my over-stuffed computer bag.

“You’re a day early. I wasn’t prepared to see you,” she chided me, half apologetic, half critical.

I grasp the Moleskin planner tightly, resentfully in my hand and wend my way further down the bookstore’s overstocked aisle, looking, longing for the unlined, undated blank pages of other journals.

The soft leather warms my leg. The jazz streams through my brain, as I reach for my jacket, realizing the autumn sun no longer caresses my shoulders.

Four unlined, undated pencil and eraser smeared pages later, I place my new soft leather-bound journal in my bag, mount my bicycle, and follow my own long shadow back home again.

The Coup

October 23, 2014

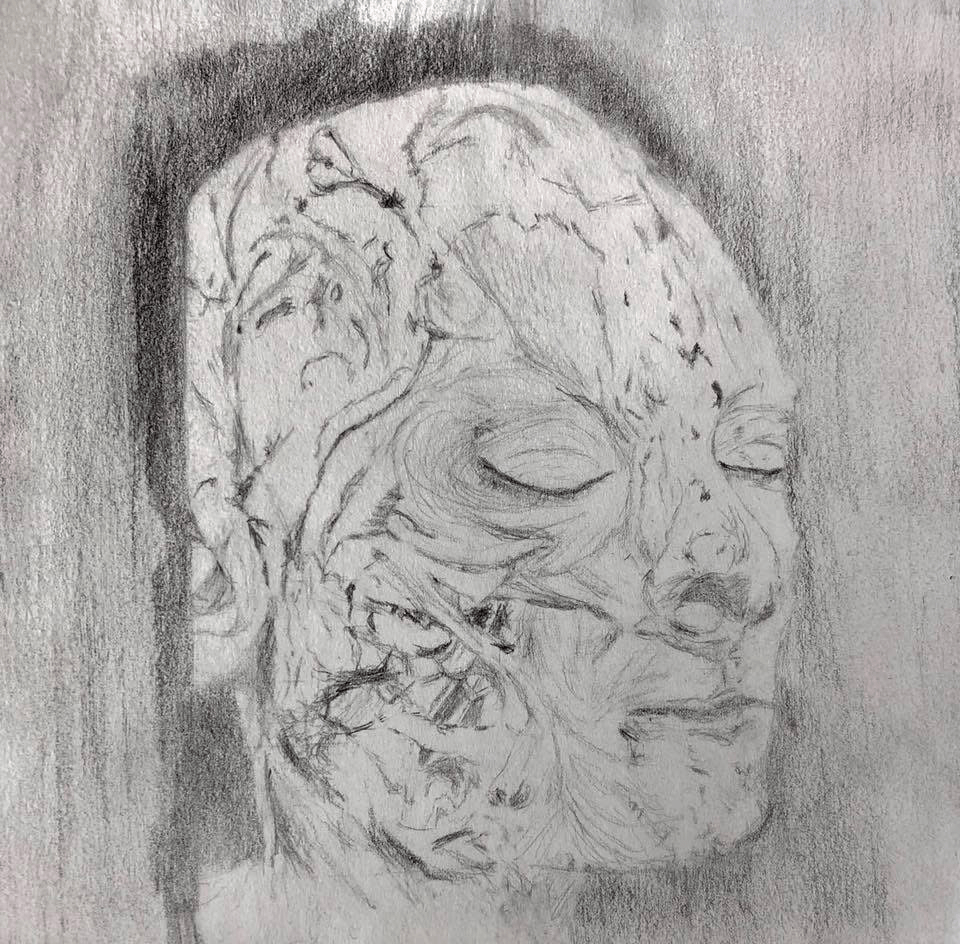

“Your injury is known as a ‘coup-contrecoup’,” she casually informed me as I struggled to record the outcome of the battery of tests she had administered over the past several appointments.

My mind immediately jumped back to my favorite lecture, my favorite period of art marked by rebelling citizens fighting aristocrats who were entirely out of touch with their day to day menial existence, those tumultuous late Eighteenth through Nineteenth Centuries which gave birth to artists Jean-Jacques David, Giroux, Millet, Degas, Monet, Dore, Manet; composers Beethoven, Wagner, Chopin and Stravinsky, as well as a string of others that my brain no longer conjures…images, names, dates, battles, concertos and exiles which literally have slip my mind.

“I finally understand the phrase, ‘overdoing it’,” I explained to my physical therapist, ticking off a short summary of the mental, social, physical and emotional strains from the previous day that rendered me incapable of executing the simple tasks in which she had just instructed me.

The intense two hours I spend with them exhaust me, and I have learned to laugh at the numerous boxes of tissue strategically placed throughout the rehabilitation center.

A quick search of frontal lobe functions yielded the following list: “Executive functioning and judgments, Emotional response and stability, Language usage, Personality, Word associations and meaning.”

For me, self-directed laughter quickly follows upon the heels of a bout of tears, those unfamiliar objects that too often trace a path down my cheeks since the injury.

“Coup: a sudden, violent, and illegal seizure of power from a government,” a simple Google search yields.

The words “sudden, violent…seizure” elicit those dreaded, seemingly inescapable salty drops. Again.

For those who know me best, to learn that my brain has executed its own coup would not be surprising since I have always been known for my independent, rebellious nature. That I am unable to actively engage in my own “Executive Processes” carried out by my damaged frontal lobe remains as equally ironic since I have likewise always scorned any hint of imposed positions of leadership.

Every ounce of my smallish frame exudes unconventionality, and up to this point in my life, I exalted in my own defiance.

The diagnoses emerge slowly, and with each new revelation have come a new symptom or two.

“Your vestibular crystals are at least still intact,” she reported after removing the goggles from my eyes that from my perspective had magnified my eyebrows, highlighting a grey one I had previously not noted. “That means we won’t have to reposition them but will have to retrain your brain to interpret the signals your inner ear canals are sending.”

Opening lines of communication then. One of my fortes, right up there with submitting to executive orders. Joy.

She continued introducing me to the battery of visual tracking exercises, instructing me to always focus on the purple she printed on a card, reminding me to remain cognizant of my symptoms. “As if I could do otherwise,” I comically noted, adding, “Hm…the ‘box’ has a lovely purple shadow the closer I hold it to my chest.”

“What do you mean?” she asked.

After explaining that the word on the card, “BOX,” appears to have a shadow when placed in my lower central field of vision, she quickly informed me, “That’s a symptom,” adding it is “double vision.”

“Leave it to me,” I chuckled, “to always see outside the box.”

“I want you to begin reintegrating yourself into social settings,” the cognitive therapist instructed me. “The process may be easier if you wear earplugs. You know, the squishy ones that some people wear so they are able to sleep better?”

“The kind we are required to wear on the tarmac?” I retorted.

“Oh…yes,” she awkwardly noted, adding, “Perhaps earbuds playing familiar classical music or soft jazz might work better.”

“Coup: a notable or successful stroke or move.”

“Hold on for just a minute,” I tell him. “I am using my earbuds for the first time.”

After squeezing the mic, I am startled by strains of Beethoven. Although I am unable to identify which symphony, I ask, “Is that your music or mine?” recalling his love for the composer.

“What music?” he asks, as tears of frustration begin to well up in my eyes.

“I don’t know. I can’t remember,” I respond. He frequently challenges me, asking me to recall the minutia that once shaped our lives.

“It must be yours,” he notes, adding, “Sometimes when you plug in earbuds, iTunes will automatically launch.”

I quickly direct my gaze toward my mic, hoping he hadn’t noticed my all-too frequent tears, attempting to focus on the double-visioned “Y” resting against my chest, and then fumbling with my keyboard to pull up iTunes so we may continue our conversation without Beethoven’s accompaniment.

My favorite Humanities lecture somehow incorporated Beethoven’s music and personal letters, comparing them with the art from the time period that had been wrought with political rebellion, an ethos of strengthened sense of individuality and heightened spirituality. But now, even when I look back at my lecture notes, I am unable to recall the correlation, cursing myself for not clearly delineating my thoughts or clearly communicating my intentions.

“Though still in bed, my thoughts go out to you…now and then joyfully, then sadly, waiting to learn whether or not fate will hear us – I can live only wholly with you or not at all,” Beethoven wrote to his lover on July 7, 1812. “Yes, I am resolved to wander so long away from you until I can fly to your arms and say that I am really at home with you, and can send my soul enwrapped in you into the land of spirits,” he continued, further entreating, “Oh God, why must one be parted from one whom one so loves. And yet my life…is now a wretched life – Your love makes me at once the happiest and the unhappiest.” He concluded, “At my age I need a steady, quiet life – can that be so in our connection?”

“Remember when we watched a movie together, making sure we pushed ‘play’ at exactly the same moment?” I ask. “Perhaps we may be able to do that with music.”

“Too much work,” he replies.

This time it is my turn to challenge him. “Which movie was it?” I ask, hiding the fact that I didn’t recall either.

That’s the pleasure of growing old with a friend. There comes a point when both parties, for whatever reason, begin forgetting what were once the important details upon which any relationship has been built.

“We both forget much,” I laugh, playfully adding, “Why do we even bother having these conversations?”

“You realize that’s all is it, right? You are only holding onto what is comfortable, what is familiar,” he insists.

“So much of what was once familiar is gone,” I wryly think to myself, again fighting the tears. “No, it’s much more than that,” I argue aloud, suddenly content that he chooses to seamlessly shift to another subject.

“You’ll be able to find a quiet corner in which to sit wherever you go. Don’t forget to use your planner to record things like what you’ve eaten, what time you’ve fallen asleep, what social engagements you’ve had, things like that. They all impact how well you are able to respond to different stimuli,” my physical therapist suggested.

I hastily jot down a few notes in my journal, realizing the warm autumnal afternoon sun has again begun to set on another day. As I walked with my girl, punctually following the schedule I had set for myself that day, I realized I had once again forgotten to eat lunch, so I had stopped for an early dinner. I remove an earbud from my ear long enough to thank the waitress, and head back, passively following my girl, absentmindedly listening to strains I was able to identify as Beethoven’s.

Something in the music’s swell strikes a chord of familiarity, stirring a faded memory. “Oh, yes. It was ‘Immortal Beloved’,” I inform no one as I head into the sunset.

“Forever thine

forever mine

forever us.”

Touch

November 04, 2014

“Stay still, TG,” she hissed. “Every time you move, you wake me up again.”

When my mother first began working overnights at the local diner after I entered kindergarten, she would stack books or crayons and a coloring book on the bed beside her when I would arrive home from my half day at school.

“Watch,” my brother told me, comforting me when he found me crying because I had colored every page in my coloring book. “Take a plain white scrap of paper and make your own coloring book page. Just draw one long line with the black crayon. Let it loop over itself again and again, then connect it back to your starting point. Then color each section a different color. It’s much better than a coloring book anyway because it is your own, not someone else’s picture.”

By consoling me, he taught me to create my own lines, my own contours, my own design.

I had likewise as independently learned to speak through reading, so by the time I was three, I avidly devoured books, losing myself in stories for hours.

Even though I had discovered words early, I spoke infrequently, content to squander away my hours in written words rather than those spoken, learning my overly formal sentence construction from books rather than casual conversation, mimicking the Romantic, flowing sentence structure of the Brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Anderson, and adopting the truncated speech patterns of Charlie Brown’s friends from my other favorite reading material, “Peanuts.”

The noise of the turning page or the motion of my reaching for another crayon disturbed her, so even these activities quickly ceased, and I learned to remain perfectly still beside her, matching my breathing rhythm with hers, deathly still, losing myself in my own imagination, watching fairy-like motes of dust float through the room in the late afternoon autumn sunshine softly filtering through the nearby window.

“You’ll have to lie as still as possible for twelve to fifteen minutes,” he assured me.

“My sister is a blockhead,” he declared each time he introduced me to a friend. “No, seriously, feel the top of her head,” a feat easily, playfully executed because of my unusually short stature. I would obligingly, laughingly lower my head so my new acquaintance could freely access the sharp angle located on the top, back part of my skull.

They would quickly withdraw their hand after locating the distinctive, square shaped head as my brother and I would exchange glances, break out in simultaneous laughter, reveling in my freakishness.

“Hey, look!” my brother exclaimed while flipping through a compilation of Charles Schulz cartoons. “Lucy calls Charlie Brown a blockhead every time he falls for her football trick,” he exclaimed, pointing to the strip in which Charlie, bereft of a football helmet, lies sprawled on the field after exerting all his energy in a vain attempt to kick Lucy’s proffered, then hastily withdrawn football. “Only difference is,” my brother reminded me, “Charlie has a perfectly round head, unlike you!”

“Take a few deep breaths before we begin,” he further instructed before adding, “I will lower this helmet-shaped guard. Don’t worry. It won’t actually touch you.”

The deep breath I take is one of relief, not preparation for the enclosed space of the MRI.

“You are wearing a helmet when you ride your bike, aren’t you?” my niece critically asked when I proudly shared with her my soft green leather journal.

“Well, no, I can’t seem to bring myself to having anything touch my head,” I responded, recounting how when the physical therapist first touched my head, it seemingly spun in her hands while frustrated, frightened tears streamed down my face.

Seeing my tears, she had quickly withdrawn her hands, and I immediately replaced them with my own, a gesture she identified as “grounding,” assuring me, “Almost all TBI patients do it. It seems to stop the spinning.”

I took a few deep breaths to take me back to my baseline, which on a scale of 0 to 10 usually perches around 6, our way of gauging how dizzy I am before beginning the various cognitive or physical exercises.

“If your level is higher than 6 at the beginning of the day, don’t push yourself, and don’t let it soar any higher than .5 or 1 point at the most. If you do, you’ll find yourself curled in a ball in a darkened room,” she reminded me. “Let me take you to those higher levels, but don’t go there yourself.”

“Twist them toward your nose as you insert them,” the technician informed me, noting my struggle to put the squishy earplugs into my ears.

“Oh, I know how to insert them,” I laughed, adding, “but this is the first time I have done it since my last day at the airport.”

As the machine began rolling me into the cavernous tunnel, I found myself breathing to the rhythmic whirl of magnets circling my head.

A few minutes later, I emerged into the warm Colorado, holding 96 images that reveal the odd shape of my head.

“You should paint a self portrait of your brain” a childhood friend encouraged me after I mentioned I had proof that yes, indeed, I DID have a brain. “That way we can all see what is on your mind.”

“Oh,” I replied, “No one wants to see what is on my mind!” knowing that very little, really, remains there.

“Kiss her, you blockhead,” an exasperated Sally yells at her brother in the animated version of “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown.” The little red-headed girl had finally revealed her feelings to Charlie Brown, kissed him on the cheek, and walked away, embarrassed by her own forwardness.

“Don’t you trust anyone anymore, Charlie Brown?” Lucy cajoles him. “Has your mind become so darkened with mistrust that you’ve lost your ability to believe in people?”

And he falls for her trick again….

With my newfound phobia of being touched, my fear may leave me figuratively lying flat on my back, alone, staring at the dust motes floating in the autumn sky, silently screaming, “AAAAAUUUGGGHHHH. Oh, good grief. I fell for it again.”

Smudged

November 11, 2014

I smiled at the smudge running from the tip of her forehead to the tip of her nose, the one that perfectly illustrated her point. “What?” she grimaced, noticing how close to the edge of laughter I was.

“Nothing,” I responded, knowing she always felt as self-conscious of her image as she did her art.

She had been the best, most realistic artist I have ever had the pleasure of meeting, her style lost in the abstract images most popular in her crowded art classes.

We passed hours together, singing loudly, laughing raucously, loving freely under the gaze of her brilliant blue morning glories that engulfed a decaying wagon wheel, “a gift for a friend, though I will probably never give it to her,” she absently declared, glancing at it harshly above her ever-present sketch book.

Under her tutelage, I learned to love the smell of linseed oil, to embrace the ineffable presence of dust or smears of paint, to mimic the way a quick but gentle stroke of the brush or hand could blend otherwise unblendable mediums.

Following the spontaneous, high-heeled onslaught of pinecones stingingly thrown at one another, we clamored back into the convertible, top down, music blasting. We hugged the curves tightly, speeding through the straightaways to rapidly reach the next challenge of the mountainous hairpin arcs that split through the pines on each side of the canyon.

Heaven.

One of those peculiarly poignantly sublime moments in which one could’t help but think, “I want it to be like this the moment I meet my death,” a fleeting thought accompanied by Pink Floyd soundtrack exploding from the speakers in the back seat.

“My grandmother attended the Institute one semester,” she explained, adding that after her grandfather died young, her grandmother had used her education as a springboard for her career, “Catering to the overly wealthy homeowners sparingly sprinkled across Denver” following the Depression.

“You’d better begin making art,” she sternly commanded as I walked out of the room, sensing that somehow I wouldn’t get the job she had posted as office administrator.

“She hired someone with more experience,” my niece informed me after I had received the letter of rejection. Somehow managing classrooms, academic advising, and walking the tight rope of administrative bureaucracy didn’t translate well to office management.

“Here they are!” he triumphantly exclaimed as he picked up another handful of soot. He opened his little hand, revealing two vehicles, blackened by fire with slightly melted wheels. From the ashes, we started yet another collection of cars, those tiny steel things for which we spent hours building kingdoms in the sand.

Charts

November 11, 2014

“How would you deal with a president of an organization who has chosen to extract himself so thoroughly that he remains only a figurehead with a title?” he asked.

“Remember whom you are asking,” I reminded him, adding that throughout my life I had balked against untoward expressions of authority.

“No, that’s specifically why I am asking you to ponder the circumstances,” he explained, chuckling mischievously.

“Hey, teachers, leave them kids alone.”

When the first subtle sounds of a helicopter emerged from the fifteen-foot-tall black monoliths positioned around the all-purpose room serving over 1,000 students as P.E. classroom, band room and cafeteria, a simultaneous, boisterous cheer would erupt. The gymnasium floor was reserved for our championship basketball team, whose lineup included a budding Blair Rasmussen and his equally tall and talented brother.

The lyrics repeatedly blared loudly from the cafeteria speakers, becoming an angry motto for an entire generation of rebellious high school students.

“Is anybody out there?”

“What do you do your first day of school?” a young teacher asked on the art teacher’s forum.

“Establish the rules and seating chart,” one responded.

“Begin introducing elements of art,” another wrote.

“Have the students draw a quick self-portrait,” another responded.

“I introduce my favorite song, Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall,’ explaining it is my theme for life. I then encourage them to bring their own favorite ‘poems’ set to music so we may begin a cross-curricular exploration of word and image.”

“I have become comfortably numb….When I was a child, I caught a fleeting glimpse….I turned to look, but it was gone….The child is grown. The dream is gone.”

“TG, go wash your hands. You are covered in soot,” she growled.

My brother and I had been sifting through the incinerator in the alley behind our house, searching for the toys she had me carry out to the fire while my older siblings were at school. “Yes, throw in Terry as well,” she demanded, as I clutched the foam, terry lined tiger to my chest while tears streamed silently down my cheeks.

“Metal doesn’t burn,” my brother insisted as he sifted through the ashes. “Bet they are still in here somewhere,” he defiantly added. “We bought them with our own allowance. If I find them, I will share.”

“So you thought you might like to go to the show. To feel the warmth…and space cadet glow. They sent us along as a surrogate band. We’re going to find out where you fans really stand. There’s one in the spotlight, he don’t look right to me. Get him up against the wall.”

“Charcoal is one of the more difficult mediums to use,” she explained as she tediously, meticulously applied the shading to her portrait of yet another rock and roll star she would add to her burgeoning, overstuffed portfolio. “It tends to go places you don’t want it to go. You don’t control it. You manage it,” she added as she glanced over her sketchpad.

Tossed

November 12, 2014

“When you write, picture your audience, and frame your essay with your readers in mind,” my freshman English composition teacher told us.

After grading our first essays, he pulled two of us aside, asking to meet with him independently to further develop our narrative voices. “I don’t like teaching upper level composition courses,” he informed us, adding, “I prefer essays that are less structured, more expressive. Neither of you need the grammatical instruction your peers need, so our meetings will concentrate more on stylistic elements contained within the rhetorical framework of the assignments.”

Although I would later to go on to teach his courses once he retired, adding the advanced formal thesis of the upper level course to my dossier, like him, my first love remained with the five shorter essays in which students could develop their own narrative voice within the loosely structured parameters, the same loose, narrative parameters of self-expression I nurtured in my art students.

“Draw from your passion, the feelings of love you embrace within your own selves,” I encouraged them.

Lessons taught, but often rarely internalized.

“How do you spell ‘premier’?” I demanded of her, frustrated that my butchered attempt yielded “no suggestions found” on my phone’s spell check feature.

“Wait. What?!” she exclaimed. “How many times did you count me down for spelling in your class? You did get hit hard, didn’t you?” she joked.

That’s the joy of teaching Higher Ed: your students easily slip into friendship once the professional relationship has ended, and this evening a former student and I had just enjoyed the premier of a documentary a friend of hers had produced.

She and I had both been tossed about over the past few years, blowing our separate ways, now facing one another after a prolonged absence, sporting nearly exactly the same style of glasses and bright red shirts designed to reveal just enough but not too much. After laughing and hugging, we had picked up exactly where we had left off, somewhere between our rural town where we had raised our children and the adventures that had brought us close without ever touching.

“Yes, I know. Time to teach myself a few lessons, I suppose,” I responded, quickly fighting the usual stinging of the eyes that accompanied my frequent frustration.

“Mother taught us well how to guard our emotions,” my sister wryly noted when I warned her that I now cried much more freely than I ever had before. “Throughout the years, I have learned tears aren’t always a bad thing,” she comfortingly added, smiling through her own tears as she greeted me for the first time in over two years.

Sequencing. Jumping from one topic to another. Inability to concentrate.

Difficult pills to swallow for someone who had always been hyper vigilant, obsessively organized.

“I gave him my motto, ‘I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way’,” she told me after we had passed a few hours together.

“You’d be fun to draw,” I told her while viewing a few of her latest photos. “I’m afraid I’d do it badly. I’d Picasso the hell out of you, but that would leave you torn and fragmented. Your beauty deserves to remain whole.”

“I look better abstract,” she smiled quickly in response. “Leaves more to the imagination!”

“Or the wrecking ball,” I ruefully added.

“I give my unconditional approval,” she replied.

“I am sure that’s what many of Picasso’s models said, but he was good. I just admittedly can’t draw a human form if my life depended upon it,” I argued.

“Soooo draw what you see… In your heart… Mind’s eye,” her voice echoed back to her former instructor across the years that had never truly served to separate us.

“Very good job, one of the better jobs you have done to let me know how you feel,” he noted after reading one of my long-winded, poetic manifestos.

“Perhaps the hit on the head has knocked some sense into you,” my brother playfully asserted.

Perhaps it has.Tossed

November 12, 2014

“When you write, picture your audience, and frame your essay with your readers in mind” my freshman English composition teacher told us.

After grading our first essays, he pulled two of us aside, asking to meet with him independently to further develop our narrative voices. “I don’t like teaching upper level composition courses,” he informed us, adding, “I prefer essays that are less structured, more expressive. Neither of you need the grammatical instruction your peers need, so our meetings will concentrate more on stylistic elements contained within the rhetorical framework of the assignments.”

Although I would later to go on to teach his courses once he retired, adding the advanced formal thesis of the upper level course to my dossier, like him, my first love remained with the five shorter essays in which students could develop their own narrative voice within the loosely structured parameters, the same loose, narrative parameters of self-expression I nurtured in my art students.

“Draw from your passion, the feelings of love you embrace within your own selves,” I encouraged them.

Lessons taught, but often rarely internalized.

“How do you spell ‘premier’?” I demanded of her, frustrated that my butchered attempt yielded “no suggestions found” on my phone’s spell check feature.

“Wait. What?!” she exclaimed. “How many times did you count me down for spelling in your class? You did get hit hard, didn’t you?” she joked.

That’s the joy of teaching Higher Ed: your students easily slip into friendship once the professional relationship has ended, and this evening a former student and I had just enjoyed the premier of a documentary a friend of hers had produced.

She and I had both been tossed about over the past few years, blowing our separate ways, now facing one another after a prolonged absence, sporting nearly exactly the same style of glasses and bright red shirts designed to reveal just enough but not too much. After laughing and hugging, we had picked up exactly where we had left off, somewhere between our rural town where we had raised our children and the adventures that had brought us close without ever touching.

“Yes, I know. Time to teach myself a few lessons, I suppose,” I responded, quickly fighting the usual stinging of the eyes that accompanied my frequent frustration.

“Mother taught us well how to guard our emotions,” my sister wryly noted when I warned her that I now cried much more freely than I ever had before. “Throughout the years, I have learned tears aren’t always a bad thing,” she comfortingly added, smiling through her own tears as she greeted me for the first time in over two years.

Sequencing. Jumping from one topic to another. Inability to concentrate.

Difficult pills to swallow for someone who had always been hyper vigilant, obsessively organized.

“I gave him my motto, ‘I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way’,” she told me after we had passed a few hours together.

“You’d be fun to draw,” I told her while viewing a few of her latest photos. “I’m afraid I’d do it badly. I’d Picasso the hell out of you, but that would leave you torn and fragmented. Your beauty deserves to remain whole.”

“I look better abstract,” she smiled quickly in response. “Leaves more to the imagination!”

“Or the wrecking ball,” I ruefully added.

“I give my unconditional approval,” she replied.

“I am sure that’s what many of Picasso’s models said, but he was good. I just admittedly can’t draw a human form if my life depended upon it,” I argued.

“Soooo draw what you see… In your heart… Mind’s eye,” her voice echoed back to her former instructor across the years that had never truly served to separate us.

“Very good job, one of the better jobs you have done to let me know how you feel,” he noted after reading one of my long-winded, poetic manifestos.

“Perhaps the hit on the head has knocked some sense into you,” my brother playfully asserted.

Perhaps it has.

Resolution

November 19, 2014

“How are the on-line exercises coming along?” she asked at the outset of our last session.

My assigned cognitive rehabilitation following a TBI entails a number of simple, quick computer-based games in which patients are able to track their progress, including their performance based upon how they compare with other people their age.

“I have improved. I rather enjoy the visual exercises, including the ones where I match the shapes that look like puzzle pieces. It reminds me of my childhood, but I believe I would still prefer to work a real jigsaw puzzle,” I responded. “I continue playing Words with Friends, and I am enjoying the ‘Pop Words’ app you recently recommended. Do you happen to know any similar apps for math?”

“I have a whole book of math worksheets,” she informed me, reaching for a well-worn workbook on her shelf. By the tattered cover, I assumed a number of her cognitive patients had likewise complained of losing their ability to compute.

“Do you know a good website with math puzzles?” I had asked a former colleague a few days earlier. “Something simple, fun, yet not too childish, emphasizing the very most basic skills.” In my recent world consisting primarily of artists who scorned numbers, it seemed natural to turn to a community college instructor for potential adult-level basic math sources.

“I don’t know of any offhand, although if you Google math skills you will probably find one you like,” he responded, adding his search had yielded ixl Math, which looked, according to his assessment, “decent.”

I clicked on the site, wondering to which level my skills may have declined, disheartened to realize that after clicking through the upper elementary ones I felt overwhelmed, then further resolving the search would probably be easier if I started at the lowest level, kindergarten.

I rushed through the simple questions as quickly as possible, challenging myself, confident I could at least skip to the first grade set. After I responded to 50 simple addition problems, I glanced at my score. I was sitting at 68%, a failing grade according to my old English Composition syllabus.

I shut my laptop resolutely, a gesture I have learned when faced with the too-frequent feeling of frustration.

As she watched the tears well up in my eyes when I first glimpsed toward the three-column addition and subtraction problems filling the simplest pages in her workbook, she quickly began flipping through it to see what else she may have, adding, “I am afraid that is as simple as they come in this book,” suggesting I begin with the page on adding coins.

“No, because of the manipulatives, I seem to be fine counting change,” mentally adding that my skill had been tested since my workman’s comp won’t directly deposit my checks into my small town bank located four hours away. Consequently, since the injury, nearly every time I make a purchase I have to use cash.

“I will make basic addition and subtraction flash cards. Perhaps the manipulation of the cards themselves will help me redevelop my skills.” After all, I reasoned, I had successfully learned two foreign languages by writing out stack after stack of vocabulary terms.

“I would purchase them instead,” she quickly added, noting, “You won’t want to accidentally learn them incorrectly.”

I grimaced, though quickly acknowledged the accuracy of her suggestion. “I may as well also pick up multiplication and division cards,” I noted, jotting down a reminder in my ever-present planner.

“I would hold off on that a bit,” she cautioned, adding “Those skills are more taxing. You may find yourself frustrated.”

I obligingly crossed off multiplication and division cards from my shopping list.

“Jigsaw puzzle or Sudoku?” I texted my daughter from the bookstore while staring at brightly colored boxes of Legos, jigsaw puzzles, and pricey wooden blocks. I juggled two boxes of simple math flashcards in my hands, reminding myself not to slip them into my purse to clear my hands as I reached for my phone.

I had never been a big bag lady, reserving my larger handbags for three-day out of town trips instead. Since the injury, I have wrestled against an inclination to carry my wallet, my phone, my glasses or my planner in one hand, forgetting that I tote my large purse slung over my shoulder. Old habits die hard, but after one of the first days following my injury in which I left my wallet at each of the four checkout counters I had visited, I quickly acknowledged the sagacity of my cognitive therapist’s suggestion that I begin carrying a larger purse.

After five months, I have now trained myself to put whatever is in my hands back into my purse so I won’t leave it behind, but while shopping, that presents an additional fear of accidentally slipping a purchase into the oversized purse while walking through a store.

The problem is easily addressed in a grocery or discount store since I have trained myself to always use a shopping cart, even if my purchases consist of a gallon of milk and a tube of lip-gloss. But boutiques and bookstores seem to be less accommodating—an odd practice, since the lack of convenience may limit the number of purchases a single customer is likely to make.

“You should begin playing Sudoku, mom,” my daughter had encouraged me while she and her mathematic major boyfriend walked through a bookstore with me years ago. “I think you would enjoy it. You are flying to and from Chicago often enough that you would have plenty of time to play them while waiting in the airport or while on the flight.” As usual, she was right, and I purchased the same book for both of us, whipping through mine quicker than she and her boyfriend had been able to do, transitioning from “easy” to “challenging” to “mind-boggling” without really noting the progression, pleasantly surprised when she had noted how quickly I had filled the pages.

“Jigsaw. I am afraid the Sudoku may frustrate you,” she responded.

I frowned, realizing once again those voices outside of my own empty head were right, and resolutely reached for the cardboard box rather than the paper-back book filled with numbers.

Helpful TBI Link:

Using Tools

November 20, 2014

“How do you do that?” my daughter indignantly exclaimed when my youngest son picked up piece after piece and placed them directly where they belonged on the increasingly larger section of the puzzle he was forming in the bottom of the puzzle box.

“I had a great art history teacher who taught me to study color, hue, texture and shape,” he laughed, glancing at me, acknowledging that I had the pleasure and honor of teaching him and his friends at our community college.

Together, they had selected a puzzle to help them through the last few stressful weeks of finals, and it stretched, unfinished, across the coffee table in the apartment they shared during my son’s last year at the University of Colorado.

Following the astrophysics graduation ceremony in which my son stood beside a soon to be retired star projector at Fiske planetarium, as a family we turned to tackle the bigger task of piecing together our fractured lives over the small cardboard shapes strewn in a series of boxes and casserole pans. We silently passed them back and forth, juggling the pieces, enjoying the companionship inherent in completing a common goal; anything ranging from assembling a tent, putting together a 1,000 piece Lego set to rebuilding our home piece by piece after our Christmas fire. Working together and playing games had always been our family’s favorite pastime.

“Ok, smart-ass, how are you going to get your 20 piece section onto the table?” she taunted.

“Oh, that’s easy,” he flippantly retorted. He knew his way as well through the kitchen as he did the tool shed, having spent years tagging along behind me as I shuffled through them myself. He had grown to be as avid of a DIYer as I was, and when he rose from the table, he emerged from the kitchen wielding a flat, large metal pancake turner, and proceeded to scoop up the disconnected puzzling mass and place it specifically where it perfectly attached to the connecting frame.

She shook her head in mocking disgust, and retreated in unspoken admiration to her corner of the puzzle.

“Use whatever tools are necessary to get the job done,” my college math instructor had informed us, understanding our reluctance. When I had returned to college, I was almost twenty years removed from my last high school math class, so I was relieved she allowed calculators. “As long as you understand basic math functions, there’s no reason not to use them,” she assured us. “And if you find yourself spending hours on a single assignment, understand you will have reached your learning threshold. Step away from your work, exercise a bit, and return. You will find you will think more clearly because you won’t be as frustrated.

“I want you to continue to develop the skill of writing under pressure,” my English Composition professor told us after our first few private sessions. “You will have to report to our regular class on the days I have assigned in-class compositions. It is too easy to rely upon grammar and spell check when composing on a computer. You need to know how to proofread and correct your own material since other instructors have you write in-class, time restricted essay exams.”

We exchanged glances, chuckled, and showed him page after page of hand-written material we had jotted, torn apart, scribbled through, and later shared as we had prepared our 3-5 page, neatly typed compositions.

Fearful of his scorn, she and I had met separately to critique one another’s work, piecing together our submitted essays from pages of brainstorming, writing, rewriting, and still unsure of our first attempt at appeasing “No-A Conway.” The hours we had devoted to a single assignment served to illustrate how vital that skill would be for both of us.

“Traumatic Brain Injuries,” the article states, “affect Executive Functions of the brain.” Frontal Lobe injuries manifest themselves in a number of ways, including impaired social judgment and an inability to assess or correct one’s own work.

“Your word retrieval seems intact,” my cognitive therapist assured me after I handed her a stack of papers, each one filled with synonyms, antonyms and homonyms. “I see few erasures, so it appears you didn’t have many errors.” I dashed my hand across my eyes, at once relieved yet still frustrated, explaining how I had struggled to spell the words correctly, using my computer to as a spell checker, transcribing the word once I was certain of its correct spelling. “I am wont to push myself a bit,” I explained resolutely.

“Your writing is as lucid and compelling as ever,” my beloved undergrad English mentor assured me when I reported my injury. The words, though appreciated, stung. Although since the injury I write frequently, my rough drafts remain riddled with red and green squiggly lines, indicating I am entirely reliant upon tools to execute my craft.

Piece by Piece

November, 2014

As a team, we had been working furiously against the deadline, arriving at the museum late in the afternoon and working far later than I should have because of my injury. In spite of the looming deadline, we worked well together, continuing to share in light-hearted banter, but I could tell by this point the designer of Macky had become frustrated by my inability to follow directions. I smiled in return, picked up the three containers of 1 x ’s and returned to the hallway to continue the same tedious task I had tackled throughout the week.

“I am glad you are volunteering,” my cognitive therapist told me, informing me that volunteer work, while allowing me to socialize, would pose less stress than a contractual or waged position would entail.

“How are the Legos coming along?” my physical therapist asked, cautioning me to be aware of my symptoms.

“For the most part, I am spending time in an isolated hallway while constructing the smaller segments that will be used for the larger components of the installation,” I informed her, with a measure of resentment and resignation creeping into my voice.

“Don’t worry, mom,” my daughter said as she watched the project design manager show us how to assemble the smaller component. “I will show you where the pieces go in a minute.”

“We have attracted 901 visitors and still have a half hour to go before closing,” the head of the Heritage Association informed us as we watched the next group walk up toward the Legos installation on opening day. “Our goal to attract the next generation of students has been accomplished,” she added, triumphantly. “We have capitalized well upon the crowd heading toward Macky for the annual performance of the Nutcracker.”

“I am glad you like the game,” my youngest son said, after we had played a few rounds. He and I had spent the evening decorating his Christmas tree, each holding a wi controller, vying our way through Mario’s latest version of Rainbow Road. “It brings back the good times we used to have playing it after the Christmas Eve house fire.”

“Recent studies indicate cognitive skills acquired while playing video games increase active though processes,” his girlfriend added as the characters she and I had created threw turtle shells at one another while speeding down a virtual road of brightly colored blocks. The light from the Christmas tree sparkled brightly in the mirror placed behind the big screen television they had purchased a few years before, casting a warm glow that blended into a colorful yet relaxing blur of auditory and visual stimulation.

“Are you ok to drive?” he asked at the end of the evening, hugging me before I gingerly lowered myself into my car.

“Yes,” I responded, realizing how subtly the roles we assume in the game of life have shifted.

Helpful TBI Link:

http://www.brainline.org/content/multimedia.php?id=7053

Sugar Plums

November 28, 2014

“Where does this piece go?” he asked me, holding up a metal part of the newly assembled bike that glistened in the soft light cast by the nearby Christmas tree.

“Hell if I know. I guess we’ll find out if it was tomorrow on the pilot ride around the block” I responded, laughing in part because we had put off all the wrapping and assembling once again well into the late night hours of Christmas Eve.

Although neither of us wanted our children to grow up in a world wrought with visions of sugar-plum fairies, fair princesses or marching tin soldiers, we unknowingly, actively perpetrate the fiction of Santa Clause, postponing most of our Christmas gift wrapping to the late hours following our four hour round trip to and from the nearest city available to purchase toys.

The first few Christmases we shared in this manner were magically illuminated by the sheer pleasure of watching their faces brighten as they opened their packages on Christmas morning, unveiling the latest Lego set or bicycle. But the last few years of our time together as a family were marked more by the adherence to traditions long since forgotten yet enacted by routine.

We tediously wrapped each stocking stuffer, even down to single packages of gum from a larger cellophane-enclosed variety pack. Traditions designed to prolong the excitement of Christmas cheer that served at times to irritate more than delight.

“I can only handle the tedium, the smaller segments,” I informed the designer of the building we were constructing for the installation commissioned by University of Colorado Heritage Association.

After showing me how to construct a few pieces, he looked at me with impatience and suggested I return to the 3 x 6 segments I had been assembling throughout the week. “It’s ok,” he sighed placatingly. “Since this is a support beam, I will do it. I am almost finished anyway.”

Faltering Steps

December 7, 2014

“You seem to have regressed with your balance,” she noted, frowning as she scribbled a few notes on a page after flipping through my ever-growing file.

Each month, at the end of my prescribed therapy and specialist appointments, my progress is re-evaluated. We had noted a slight improvement in my ability to twist my neck in what had originally seemed to be circus-like contortions and in my visual tracking, but as I stood with my eyes closed on a soft surface, I felt my physical therapist’s guarding hands softly thumping against my back and chest as I wavered back and forth.

Discouraged, I sat back onto the firm examination table, as the perpetual tears welled up in my eyes again.

Toward the outset of autumn, I had the pleasure of riding my bike several miles a day after having passed my former physical therapist’s test of being able to stand on one foot for a minute at a time, a skill in which I had prided myself while learning Tae Kwon Do.

Returning to my bike after my injury as a means to continue developing my balance was a reward I had worked hard to earn, but not something I expected to lose once learned.

“We haven’t worked much on your balance. We have concentrated more upon your tracking and mobility,” she added with a tone of consolation.

The tears continued to flow as my mind flashed back to the simple lessons in addition and subtraction I have now begun to undertake.

“Practice standing with your feet in tandem, first with your eyes open, then eventually with your eyes closed,” she instructed as she handed me yet another sheet of paper delineating the various exercises I would have to include in my daily routine. “If necessary, hold onto a firm surface for support with just a few fingers barely touching to provide a sense of grounding. Always challenge yourself. If one exercise is too easy, add an additional component, but always listen to what your symptoms are warning you to do.”

After explaining that by the end of the summer I was able to stand on a single foot even while watering plants, I asked, “Am I going to have to continue re-learning each lesson repeatedly?” with frustration and anger seeping into my voice.

“For now, yes,” she responded, adding with a note of hope, “You may not have to once you are further along in the healing process.”

“How is the healing coming along?” my sister-in-law asked at Thanksgiving. I’d been warned by my therapists the movement at the table, the stress of preparing food, and the various sounds associated with family gatherings may prove to be taxing.

I glanced up at the video feed of orchestrated music overhead to swallow the ever-present lump in my throat. She had visited with me briefly early in the summer when I first began the healing process, but even though I am living with her daughter, she received very few progress reports.

After swallowing a few times, assuring myself that I could control the tears, I returned her gaze, explaining that I had recently undertaken the challenge of kindergarten math flash cards, laughingly adding it would be awhile before I could make sense of the college art history lectures I had delivered for nine years in our dusty Southeastern Colorado community before shifting gears and moving to Chicago to complete my Master’s Degree at the Art Institute.

“I am a bit taxed,” my nephew explained after I asked him how his project for the University of Colorado Heritage Foundation was proceeding. He and his companions had received the commission about the same time I had sustained my injury. He had been frazzled but excited when we had met shortly afterward as I volunteered my assistance, but he had not contacted me throughout the remainder of the summer.

I had lost myself in hours of therapy, and when I saw him at Thanksgiving, I realized he had lost himself in his overwhelming commission. My daughter and I once again offered to help, and this time, he took us up on the offer.

“Look,” I exclaimed while scrutinizing the details of the collaborative installation that sprawled across eight tables, “You’ve even included a dog eating leftover pizza,” adding that my girl loved walking across campus on a Sunday morning, pillaging for whatever leftover items she could devour before I caught her digging through yet another discarded pile of refuse.

All the vignettes were there: Boulder’s famed bear caught while falling from a tree, the outdoor Shakespeare Festival, the overcrowded bike racks outside Macky Auditorium, and even a prospector celebrating the birth of the University toward the end of the Colorado Gold Rush. Details celebrating the rich history of my alma mater. Walking visually through the Lego reproduction reminded me of lessons forgotten in the haze of the concussion.

“Help myself to remember new information by connecting it to old information, personal life experiences and knowledge I already have,” the instructions provided during one of my latest therapy sessions states. “That should be easy to remember,” I noted during the session. “As educator, I encouraged my students to link knew knowledge to life experiences and build upon older lessons. I am glad,” I added, “I have my teaching skills to help assist me as I learn to navigate my way through my injury.”

Every step in life leads to a specific destination, even if the steps along the journey at times may seem to falter.

Another TBI Blog:

http://www.brainline.org/content/2015/01/when-you-least-expect-it.html

Cards and Castles

December 30, 2014

“The pieces of your life seem to be falling together perfectly,” my brother-in-law quietly observed as he watched me struggle to shuffle the cards.

Every family gathering entails long hours sitting around the dining room table, bantering while throwing down cards in a rousing game of canasta.

I smiled ruefully as he added, “If your injury had occurred anywhere other than work, you wouldn’t have received the excellent medical care, you wouldn’t have had an income, and you wouldn’t have had an opportunity to dedicate yourself to your art as you have the past few months.”

As my fingers fumbled with the task which I once enjoyed almost as much as the game itself, I thought, “If I hadn’t been working the job I had taken, I wouldn’t have been injured,” adding silently, “And never mind the income is not even half what I was making at my low-paying job because of a technicality the insurance providers have capitalized upon.”

Even though the too-long hours of post-Christmas activities were exhausting, I still pushed myself to engage in the traditional activities, knowing I would pay for it later. My two year old niece and I shared naps, and, on those nights when I pushed myself too hard, early bed times. I made up a few more hours by sleeping in while the rest of the family ate breakfast. The skipped meal was well worth indulging in the light-hearted banter around the table throughout the evening.

“Who wants the chore of pairing with me?” I asked, knowing that because of my inability to concentrate, I would be more inclined to play a losing hand than ever.

“I will,” my sis volunteered, and at the same time offered to play two hands so my brother-in-law would also have a partner, also balancing her usual job of scorekeeping, shuffling, and, at the end of the game, sorting. I admired her ability to multi-task, the same skill set she had used to build her remarkably successful career in project management.

“Be prepared to lose,” I warned her, adding, “I will be unable to tally our cards at the end of each hand, much less try to keep track of what you are discarding. You’ll also have to frequently remind me of the rules as we play,” I offered to everyone gathered around the table, a statement proven true each time I believed I had the right number of cards to “lay down” the first round, a task my brother-in-law would aid in to prevent any sort of “table talk” between me and my partner.

Each evening (except one, when I was far too exhausted to walk, much less play a round of cards following a trip to a crowded mall), she would have one winning hand—the one she was playing with her husband—and one losing hand—the one she was playing with me.

In spite of the daily loss, the games served as yet another opportunity to practice basic math, and by the time the holidays were over, I boasted the ability to at least count by tens even though counting by fives remained too challenging for my basic arithmetic skill set.

“As I have reminded you, we have a year of healing. Your attitude seems upbeat,” my doctor observed once I compared the constant vertigo to an amusement park without the cost of the overpriced ticket.

“I’ve learned every new experience is an opportunity for growth, for development, and throughout my life, I have loved learning,” I responded, wryly adding, “I just never quite expected the simple skills of addition and walking would be among those lessons.”

“Just keep following the exercises your therapists provide for you,” he reminded me before leaving the office.

“You know you aren’t supposed to begin working the rest of the puzzle until we have found all the edge pieces,” he scolded me. “Mom won’t let us help if she catches you doing that.”

I frowned my response, dutifully tearing apart the section I had placed together, pieces that naturally fell together because I easily identified the similarities in texture, shape and color. Following her strict rules regarding jigsaw puzzles—or anything else, for that matter—never came easily for me, but because I feared the consequences—always too harsh for the crime committed—I begrudgingly complied.

As children, we had few toys, instead entertaining ourselves with whatever grown-up pleasures we had on hand, ranging from hours watching dust motes fall upon the spinning of the vinyl classical music as it played, perusing through discarded encyclopedias supplied by a kind neighbor, arranging rocks in my father’s garden, or passing hours piecing together 1000 piece jigsaw puzzles, gifts from the same kind neighbor. Each activity had specific limitation to which we must strictly comply.

The jigsaw puzzles were usually reserved for Christmas vacation, holding a special place of their own on a card table in the crowded living room where all eight of us children would gather around at one point or another. We first were instructed to rifle through the pieces to find those with a straight edge. We weren’t allowed to take any other piece out of the puzzle box unless it comprised the border.