Onward

The dark threatening clouds lowered;

The heavy bike fell harder

The River leans into the rock,

Carving, curling, twisting, tumbling;

A trail where beggar urchins dwell

Rhyding away the weak vermin.

Than the relentless pouring rain.

Water in the skull rises,

Seeping through forest, moss, and glen;

Enclosing, embracing, encompassing;

Inheritance: ever frozen!

Cold, wet, tired; still we pressed on.

Sisters dancing together in time,

Silent tears etching their faces;

Satan’s bow aimed at their hearts,

Guarding their brothers’ shining graves.

Determined the same way a

Market town, graveyard: hallowed ground

Slumbering near forested hills;

Three Lords supplanting the Ancient Ones

E’er awaiting their own demise.

Disfigured, hunched monarch

Led by two maidens and their cow dung,

Ancient bones were carried afar;

Borne by men married to malice,

Burning holy ones, their wives, their children!

Or a bent condemned witch

Children, Weep! Bear your tribute!

Wander the hill, after your flowers,

Plucked from meadows near the well;

Final Wulven Haven: Fallen!

Resolutely moves forward.

The inevitable journey;

All good and evil has been done,

Judging souls after their passing:

What shall be written on gravestones?

Searching longingly for love

Largest stronghold along the stones,

Twice man’s height, traversing the land

Sightless battlegods looming o’er

Ere seven rune rings united.

Or at least some acceptance,

High beacon above the green vale

Spilling secrets along the path,

Protecting windswept sojourners;

Rest, all Ancients who linger here!

But, stumbling, discovering something

Most ancient of dismal circles,

Standing erect in seclusion,

Dark precipice of heath and moor:

Alight autumn’s divinations!

Far more grand and glorious:

A cauldron boils that once was a cave,

Where roiling waters thrice appear;

In foggy mourning heed your step,

Lest your voice become mere whisper.

History, art, tradition, beauty.

Pity the king’s blind sons and daughters!

Cruelly forced to carry burdens.

Their birthright prudently hidden:

Patiently await, oh warriors!

Swaddled in the darkest cloak:

Arise from the lake, great keepers!

Four towers championing our gods,

Protecting, watching, nurturing

Embracing rituals of the people.

Perseverance. Independence.

Bathe in the pond of sacred force,

Wash away your pain and sorrow;

Silence, saddest Alkelda,

Cleanse for your journey on the morrow.

Strength. Self-reliance. Autonomy.

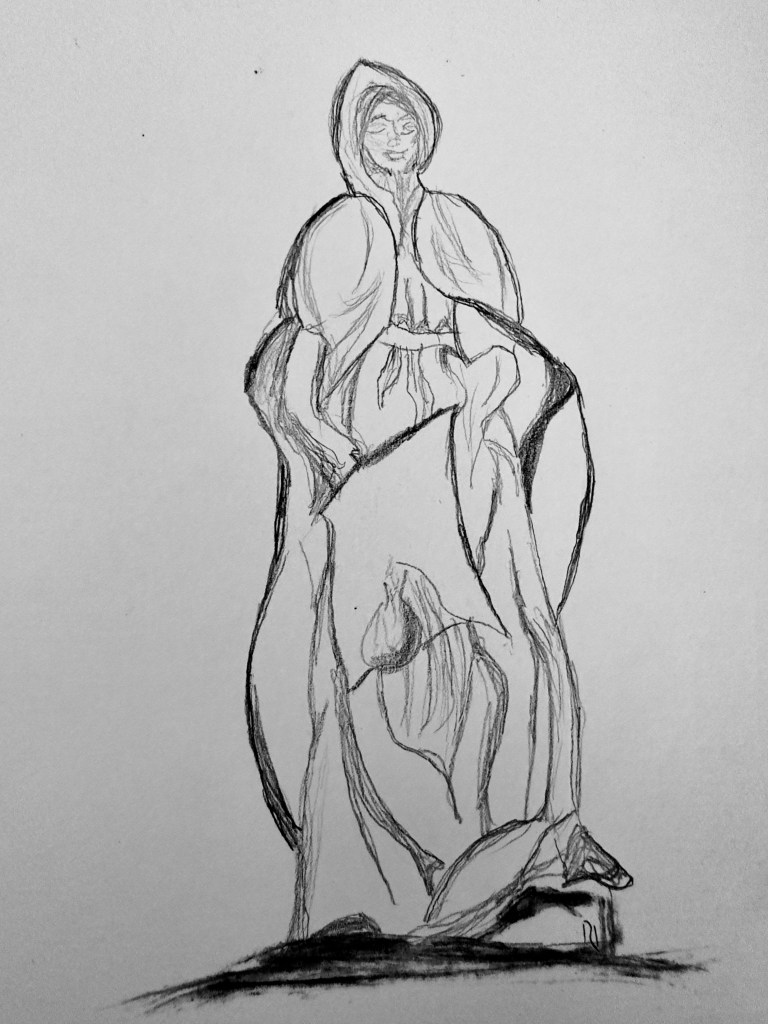

Protector, warrior, angel demon;

Patron of high-thon’d King:

Motherrood of Ælves and Wulves;

Wise Woman, Beneficent One!

We are stuttering, strutting,

Human, oxen, deer and auroch:

Blood stones ‘neath the ancient timber!

Archer and Bowman meet in the circle,

Where giants weave their wicked ways.

Disdained, slutty villains

Haltingly and fleetingly,

The Goddess Isis bends her knee,

Stubbornly refusing to reveal

Her deepest, darkest mystery.

Idling away our freedom

With deepest passion, pleasure.

iii

Mechanical Reproduction

Revolution: Barcelona (Reprise)

September 26, 2024

While working on my graduate degree at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I had observed that it takes the abject poverty of the transient alongside the obscene wealth of consumerist-driven cold capitalism to truly see, and truly comprehend, the need for Revolution. And it is best seen in the labyrinth of a city’s mass transit.

The sights and sounds one encounters on Barcelona’s train platform echo of the mournful wail of Charlie Parker’s plastic saxophone or the driving beat of Megadeath: the grating, irregular pounding of shouting passengers attempting to converse over the mingled clang of glass, steel, and electricity, the components of the city’s now sacred sites as they bustle about to worship their holy god of materialism.

Like many of the scholars in the United States who have recently found their programs defunded and have fled across the pond for greener pastures, Walter Benjamin had fled his beloved Germany to escape Hitler’s Third Reich. He and a group of scholars had attempted to cross into Spain to avoid capture, and as the troops descended upon the hotel in which Benjamin and his colleagues had taken shelter, he thrust his oeuvre into the hands of Thodor Adorno, compelling him to keep it safe, then took an envelope of morphine. His suicide, as well as the failed attempt of another exile, journalist Kosztler Atur, who was fleeing with him, distracted the Spanish officers intent upon seizing the group of Jewish exiles, allowing the others to flee safely into Lisbon.

Barcelona inhabitants abhor tourists, and for good reason. Their once affordable flats have all been purchased by developers and offered as luxurious Airbnb rentals. Too much of the lower middle class of a decade ago have now joined the throngs of gypsies, the lost souls relegated to the streets, panhandling in whatever way possible for a pittance of sustenance.

As we waited for the train that would never come because of delays further up the track from an uprising in one of the suburbs, I listened to the soft wails of a street musician and recalled portions of Benjamin’s essays. As she sang the blues, the light of the nearby “advertisements” and “the fiery pool reflecting it” created a phosphorescent glow around her. I watched as people rushed past her with their designer shopping bags and seven dollar paper cups of coffee as they peered into their bags for glimpses of those “few accessories…which cost lots of money because they are so quickly ruined,” assuring themselves that their treasures had survived the onslaught of the downpour. The expensive, sheer translucent bags broadcast to the world that they contained “the most lustrous and colorful of silks,” thereby sharing “the newest thing with” everyone else, serving as the commodity-seeker’s “triumph over the dead.”

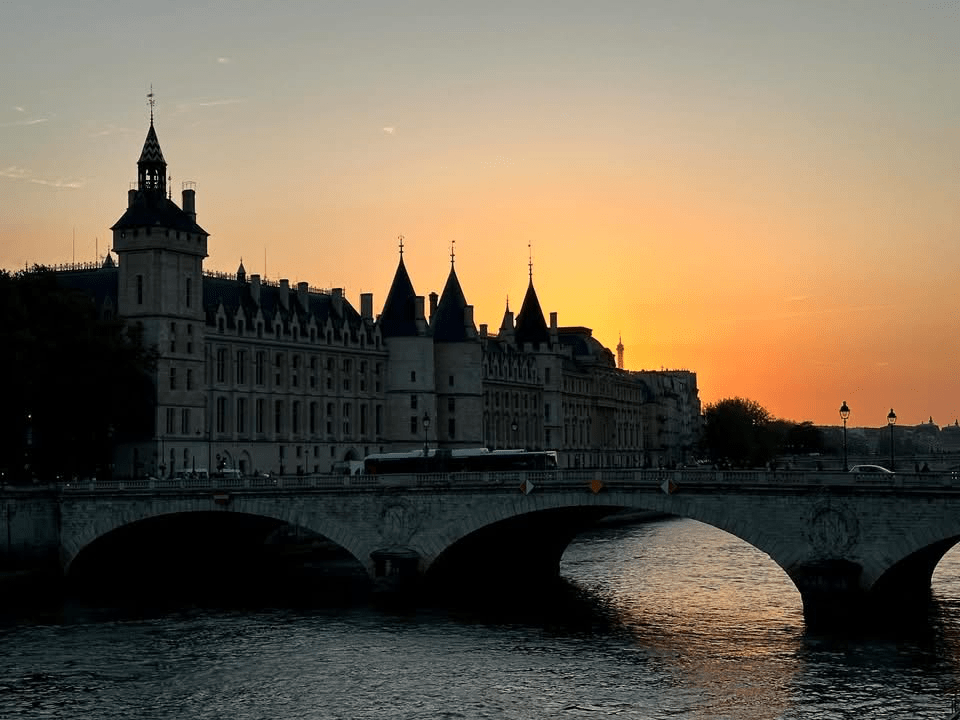

Though I had not indulged in purchasing luxury items and had declined my daughter’s generous offers to purchase a number of trinkets, both useful and ornamental, my daughter’s pack had become slightly overstuffed, and she grasped a recently acquired beautiful oversized fur-lined, pink strappy bag that was also bulging, reminding me of my journey through Europe two decades earlier when I jostled through crowded streets and airports of Paris, Versailles, Monte Carlo, Assisi, Florence and Rome protecting a delightful plaster of Paris replica of Notre Dame’s gargoyle, his head peering out of my bag the way a New York commuter’s Maltese will do now that dogs are allowed on public transit.

As we rushed toward the next train that seemed as though it would perhaps allow us to make the connections to our return flight to London, I quickly flung the bungee cord shoulder strap of my bright blue, turquoise and yellow soccer ball onto my back and boarded the overly crowded, standing-room only train, thankful that I would soon be rejoining my whining soccer ball and my service wolf-dog in my 18 foot square space, the converted ambulance that has taken me on any number of adventures as I conduct research for my eighth novel, which is set primarily in the United States. Because my space is almost as limited as the dog trailer I had shared with my Great Pyrenees as we cycled 825 miles across America, my space, my home, remains delightfully devoid of the accoutrements of materialism that too often weigh heavily upon our society.

Well. Almost devoid of clutter. I’ve still hung onto a full bookshelf of research materials for my novels….and a favorite gargoyle or two.

After all, they provide protection.

Against the Wind: Púbol

September 25, 2024

It’s like flying.

I learned the joy of soaring downhill with barely nothing above or below at a very early age. But like most pleasures, the thrill gives way to fear with age.

My comfort speed is somewhere between 6 to 12 miles per hour.

But on my first long cycling tour from Chicago lakefront to Colorado, physics of the 86 pounds of my great girl taught me once again that braking while descending is not always a wise choice. Her weight pushed us, and the first time I attempted to brake, I could feel her trailer begin to jackknife. Lesson learned, or unlearned since aging had made me fearful.

She loved speed. She would poke her head out of the trailer and howl, her ears and long fur flapping in the wind.

Or she was as terrified as I was and I had to project joy onto her to overcome the fear.

On a smooth descent, I stand with my legs locked, bend over the handlebars slightly and let the wind rush around me. I call it my Titanic pose without some icky boy stabilizing me.

The landscape becomes a blur, markings on the road become an arrow, the wind is exhilarating.

Then she passed us. She was sitting back on the seat of her bicycle, both hands engaged in peeling a banana.

The app had warned us the hill of our last day would be daunting, one shared with professional cyclists training for races or the Olympics.

“We’ll need to pace ourselves with our batteries,” my daughter advised. “There’s a cafe where we can grab lunch and recharge our batteries before the hill.”

Traveling in a foreign country can be upending.

“I don’t think I will ever leave the country again,” he said after returning from a trip to Paris. “Riding public transit, the flight, the constant low roar of language I can’t understand.”

Deal breaker. Seriously.

The two most difficult cultural barriers of Spain were language and hours for dining.

At the foot of the hill, we encountered both.

My daughter and I with our Latin training can stumble our way through French, Spanish, Italian. But Catalonian is a unique assimilation of all three.

”Comida,” my daughter said, making a gesture of eating as she did.

A shake of the head was the singular response.

Not easily thwarted, she pointed to the battery she had brought into the bodega. “May we charge?” a question met with the same response.

Fear began fomenting in the pit of my stomach.

The man stepped away, and within a few seconds a younger man appeared, graciously pointing us to an outlet then leading us to a table where he handed us a menu.

We pointed to what we wanted, and he shook his head then pointed to the bottom of the menu written only in Catalonian.

Thank goodness Google translate works better than maps.

”In typical Spanish fashion, they stopped serving at ten this morning and won’t serve again until eight tonight,” she said.

Holding up two fingers, she simply said, “espresso et leche?”

When the older gentleman presented the black elixir sans leche, we smiled gratefully.

”Now to make one ounce of soul fuel last long enough to allow our batteries to refuel….”

As we waited, another patron, obviously a regular to the establishment, stepped to the counter and took a seat on the patio with his wife. A few moments later, a member of the waitstaff took two sandwiches and a bottle of wine to them, visited for a bit, and returned, offering a challenge in his eyes as he passed our table.

Some messages are clearly conveyed without a common language.

The entire staff gathered around a table across the bodega, smoking and splitting several bottles of wine. As time passed, their gazes, tones, gestures and laughter became increasingly rancorous. When the woman stood, looked directly toward us and bent over a chair while the older “gentleman” came behind her and began crudely thrusting his hips against her backside with his eyes locked onto us, we knew it was time to go, regardless of whether or not our batteries were sufficiently recharged to get us to the top of the mountain.

Walking up the hill, if necessary, was far better than staying.

She had sped past us on our ascent, head bowed, wheels speeding compared with our slow churning. Steph and I had just laughed at our own speed. “Well, we DO have packs that indicate we’ve been doing this for days. That should give us creds, right?” she asserted with obvious doubt in her voice.

”Absolutely. Besides, I have learned early not to feel self conscious because of criticism objecting to ANYTHING I do.”

When we ascended the last bit of the mountain, we stopped. “Pretty sure the woman with the banana will be one of the best things we will ever see,” she noted with a laugh. “And compared with ANY hill in the Rockies, that was nothing” she threw over her shoulder as we executed the final switchback into Girona where we rewarded ourselves with local gelato.

Isolationism for some, it appears, is like speed: one’s ability to adapt to whatever situation arises sadly does fade with age if one is unwilling to momentarily embrace the discomfort.

”Literature is strewn with the wreckage of those who have minded beyond reason the opinion of others.”

~Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Is Anybody Out There: L’Estartit

September 25, 2024

“‘No one’, Pascal once said, ‘dies so poor that he does not leave something behind’. Surely it is the same with memories too—although these do not always find an heir. The novelist takes charge of this bequest, and seldom without profound melancholy.

~Walter Benjamin, Illuminations

The barrage of texts hit before sunrise.

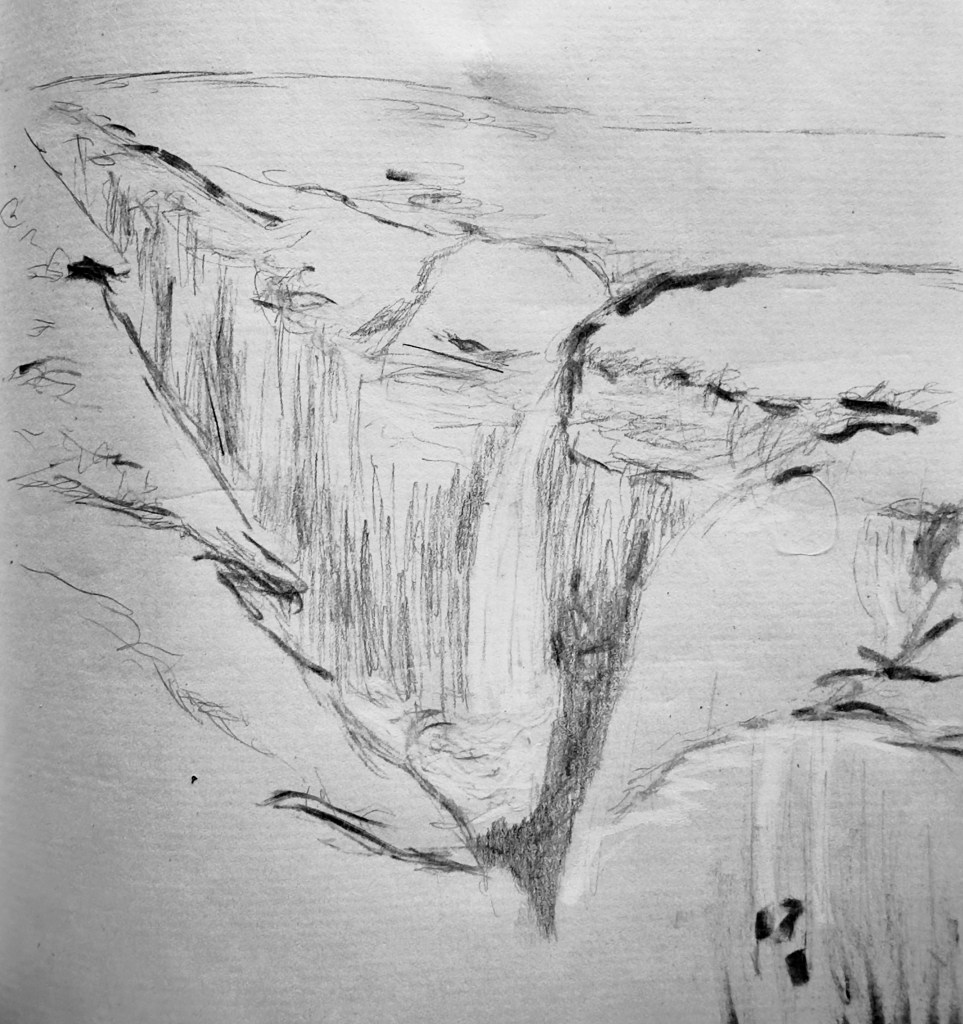

We’d wanted to catch sunrise on the water hoping we could at least glean beauty if not warmth on our last day along the Mediterranean, especially since the cliffs at the edge of the beach village had been splendidly restlessly exquisite when we had stumbled upon them long after sunset.

I’ve no idea now what the context had been, but it had all the requisite qualities of an IRC: “Icky Relationship Conversation.” To silence them, I sent a single sunrise photo, with a succinct reminder it was the morning of the last leg of our journey, then resolutely slipped my phone into my pocket with the realization I had done it again.

Learning from my students has always been the most delightful part of my profession. Somewhere along the way, one of my students has become a social media influencer, a guru of all things relational, chiding both men and women alike for wasting time on narcissistic, emotionally abusive people.

“Narcissism is rampant in Christian ministry,” my brother, a retired military chaplain, frequently notes, a veracity I freely embrace.

Admittedly my record is not good, nurtured from the start by a highly egocentric parental figure, followed by a twenty-year marriage to someone whose family exhibits genetic narcissism.

At that moment, I understood I had done it again: dedicated far too many years of emotional energy sucked into the black hole of narcissism.

“He made you feel like you weren’t good enough to keep you from finding out that you were too good for him.”

~Treytyrell8

I’d put off writing, walking, hiking, even camping in some of the most pristine off-grid locations waiting for a text, a video chat, a sign that a particular “anybody” was “out there.” I’d struggled with my voice and content, wondering whether or not it would meet with one person’s approval. I’d shaped my life (again) hoping for a huge helping of acceptance, contenting myself with crumbs of barely insinuated flattery.

Yes, I am independent. Yes, I do enjoy my singleness. But as I mounted my bicycle for the last push back toward Girona, I truly did follow my daughter’s lead and vowed to henceforth embrace my identity, my beliefs, my strengths, knowing full well how often my weaknesses had restricted my own process of becoming.

I can only hope that my words, my writing, my memories, the odd collections of tangible and intangible materials and experiences not only shape my heirs, but anyone who happens to stumble upon them as they make their own treks through life. The barrage of texts hit before sunrise.

We’d wanted to catch sunrise on the water hoping we could at least glean beauty if not warmth on our last day along the Mediterranean, especially since the cliffs at the edge of the beach village had been splendidly restlessly exquisite when we had stumbled upon them long after sunset.

I’ve no idea now what the context had been, but it had all the requisite qualities of an IRC: “Icky Relationship Conversation.” To silence them, I sent a single sunrise photo, with a succinct reminder it was the morning of the last leg of our journey, then resolutely slipped my phone into my pocket with the realization I had done it again.

Learning from my students has always been the most delightful part of my profession. Somewhere along the way, one of my students has become a social media influencer, a guru of all things relational, chiding both men and women alike for wasting time on narcissistic, emotionally abusive people.

“Narcissism is rampant in Christian ministry,” my brother, a retired military chaplain, frequently notes, a veracity I freely embrace.

Admittedly my record is not good, nurtured from the start by a highly egocentric parental figure, followed by a twenty-year marriage to someone whose family exhibits genetic narcissism.

At that moment, I understood I had done it again: dedicated far too many years of emotional energy sucked into the black hole of narcissism.

“He made you feel like you weren’t good enough to keep you from finding out that you were too good for him.”

~Treytyrell8

I’d put off writing, walking, hiking, even camping in some of the most pristine off-grid locations waiting for a text, a video chat, a sign that a particular “anybody” was “out there.” I’d struggled with my voice and content, wondering whether or not it would meet with one person’s approval. I’d shaped my life (again) hoping for a huge helping of acceptance, contenting myself with crumbs of barely insinuated flattery.

Yes, I am independent. Yes, I do enjoy my singleness. But as I mounted my bicycle for the last push back toward Girona, I truly did follow my daughter’s lead and vowed to henceforth embrace my identity, my beliefs, my strengths, knowing full well how often my weaknesses had restricted my own process of becoming.

I can only hope that my words, my writing, my memories, the odd collections of tangible and intangible materials and experiences not only shape my heirs, but anyone who happens to stumble upon them as they make their own treks through life.

Be-atch Day: L’Estartit

September 24, 2024

“Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories…. The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of the object.”

~Walter Benjamin, Illuminations

We had the beach to ourselves, which under different circumstances, would have been bliss.

We’d dreamed of it for over a year.

Our tour promised two days along the Mediterranean, and our goal had been to relax along the beach after pushing through the Pyrenees.

Silly us. We should know better.

When we arrived at the gorgeous, white stuccoed hotel, the sky was as beautifully blue as the paint and tile that popped against the brilliant white.

The tour promised that the beach was only a few miles away from our lodging, an easy bicycle ride. But they failed to provide directions on their fabulous app that had safely guided us almost 100 miles.

So we turned to Google.

Depositing our saddlebags in our room and changing into our swimsuits only took a few minutes, and the sky was still brilliant blue.

Turn after turn after turn, an easy thing to do when Spain is spotted with roundabouts especially with Google telling me where to go, we made a slight detour when we stumbled across a quaint but HUGE market. We finally believed ourselves to be headed toward the beach, an interesting feat since there were no hills, just extraordinarily flat land giving no indication that we were losing elevation necessary to take us to sea level.

About a half mile from the beach according to our erstwhile guide, the sky darkened substantially.

Within seconds, we found ourselves racing past more bodegas, a smattering of alluring granjas, and a few bodegóns, pressing forward hoping the downpour would become less relentless by the time we reached the beach where we could settle into a chiringuito, a beach-side bar.

Nothing. Even the lifeguard stands were empty.

We stood huddled under my flimsy cloth jacket attempting to pull up Google.

The screen was as untenated as the beach.

Knowing my penchant for crashing electronics and distorting Google, my daughter looked at me, laughed, and stepped about ten feet away. In spite of the rain, she pointed, “That way,” and we trudged our useless E-bikes across the sticky, mooshy sand. And of course, as soon as we arrived at a welcoming, butane heated, canopied patio, the downpour ceased.

There are times when collecting memories calls for a pitcher of Spanish Sangria with a side of sizzling tapas.

On our way back, with half of our still lusciously wonderful pomegranate awaiting us in our hotel, I plucked a few fresh olives from a low hanging branch.

”Here,” I offered, thrusting it toward my daughter, who eagerly popped it into her mouth, then instantaneously spitting it back out.

”Oh, dear god,” she exclaimed. “What was that?”

Turns out olives fresh off the branch aren’t nearly as enchanting as pomegranates.

Day two of our Mediterranean adventure was much like day one, but at least the processed olives served with our tapas and sangria at the chiringuito will become a sublime collected culinary experience never to be forgotten. September 24, 2024

“Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories…. The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of the object.”

~Walter Benjamin, Illuminations

We had the beach to ourselves, which under different circumstances, would have been bliss.

We’d dreamed of it for over a year.

Our tour promised two days along the Mediterranean, and our goal had been to relax along the beach after pushing through the Pyrenees.

Silly us. We should know better.

When we arrived at the gorgeous, white stuccoed hotel, the sky was as beautifully blue as the paint and tile that popped against the brilliant white.

The tour promised that the beach was only a few miles away from our lodging, an easy bicycle ride. But they failed to provide directions on their fabulous app that had safely guided us almost 100 miles.

So we turned to Google.

Depositing our saddlebags in our room and changing into our swimsuits only took a few minutes, and the sky was still brilliant blue.

Turn after turn after turn, an easy thing to do when Spain is spotted with roundabouts especially with Google telling me where to go, we made a slight detour when we stumbled across a quaint but HUGE market. We finally believed ourselves to be headed toward the beach, an interesting feat since there were no hills, just extraordinarily flat land giving no indication that we were losing elevation necessary to take us to sea level.

About a half mile from the beach according to our erstwhile guide, the sky darkened substantially.

Within seconds, we found ourselves racing past more bodegas, a smattering of alluring granjas, and a few bodegóns, pressing forward hoping the downpour would become less relentless by the time we reached the beach where we could settle into a chiringuito, a beach-side bar.

Nothing. Even the lifeguard stands were empty.

We stood huddled under my flimsy cloth jacket attempting to pull up Google.

The screen was as untenated as the beach.

Knowing my penchant for crashing electronics and distorting Google, my daughter looked at me, laughed, and stepped about ten feet away. In spite of the rain, she pointed, “That way,” and we trudged our useless E-bikes across the sticky, mooshy sand. And of course, as soon as we arrived at a welcoming, butane heated, canopied patio, the downpour ceased.

There are times when collecting memories calls for a pitcher of Spanish Sangria with a side of sizzling tapas.

On our way back, with half of our still lusciously wonderful pomegranate awaiting us in our hotel, I plucked a few fresh olives from a low hanging branch.

”Here,” I offered, thrusting it toward my daughter, who eagerly popped it into her mouth, then instantaneously spitting it back out.

”Oh, dear god,” she exclaimed. “What was that?”

Turns out olives fresh off the branch aren’t nearly as enchanting as pomegranates.

Day two of our Mediterranean adventure was much like day one, but at least the processed olives served with our tapas and sangria at the chiringuito will become a sublime collected culinary experience never to be forgotten.

Strong Enough: Sant Pere Pescador

September 24, 2024

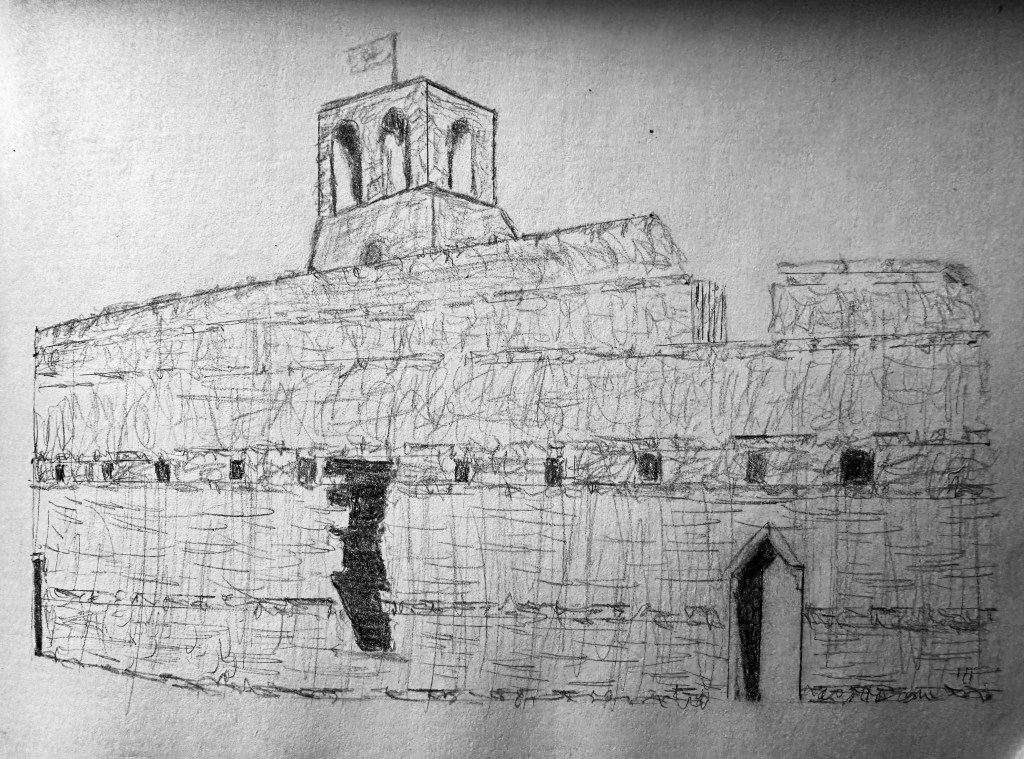

The edifice appeared on the horizon as soon as we had fully descended into the plains on our way toward the Mediterranean.

Hollywood is known for misleading viewers, and the castle on the hill, featured in the climactic scene in Kevin Costner’s version of Robin Hood, is located in Spain, not England.

A justifiable manipulation of reality. I had started my journey in Nottingham, and their castle, to be honest, really is not very intimidating, whereas the one overlooking the plain in Spain is.

Intentionally misleading an audience is an age-old trick. The edifice, visible across the entire Catalonian plains, was never completed. It loomed above the kingdom as a visible threat, a reminder of power, but an empty shell.

Not much different, really, than the Wizard’s Emerald City.

Yours. Mine. Ours.

Growing up as the youngest of eight children, by the time my mother reached me, she was thankfully over trying to create the perfect lady. Besides, she had wanted a boy, so when I began exhibiting independence and living up to my name, which was chosen from that of two of her brothers, tossing me outdoors seemed natural.

While she was the one who taught me to be strong, it was my brother and father who taught me which tools were what and how to use them. They were the ones who nurtured my passion for rocks, plants, insects, tinkering, camping and cycling (I am the only one of the combined six daughters who ever owned my own bicycle).

Living in the cramped quarters of 1000 square feet, we were known to take very long Sunday afternoon drives, which entailed open windows, dust, and careening around sharp mountain curves at high speeds.

In a lifetime before safety restraints, the eldest wrangled over the spot in the front bench seat between my mother and father. The losers then wrestled to fill the back seat, and the rest of us were tossed into the back of the station wagon, where we were jostled about like boulders tumbling down a mountain rockslide.

Once I was no longer jostled and confined into a cushioned seat with a seatbelt, throughout my life drivers have hated having me as a passenger. Not because I tell them what to do, but because at any given moment they are faced with two choices: pull over IMMEDIATELY when I request or wear vomit.

Motion sickness has always marked my travel experience, limiting access to things like busses, trains, boats and subways. Without the excess jostling I’d been exposed to in the first few years of my life, I have to always sit very still, facing the direction of travel, with my eyes directed only forward. I have ridden miles and miles through some of the most astounding scenery in the world and have been able to view very little of it.

The traumatic brain injury has for the most part reversed that. Place me on whatever kind of seat is available, but don’t you DARE jostle me or you will see me reduced to a stammering, screaming imbecile.

The first two and a half days of our ride through Spain had been perfect, in spite of the streaked backsides on the first day: challenging enough to be fun, scenic enough to be breathtaking, and I’d contentedly been a passive rider following the tire tread of my daughter, even when they included picturesquely, slowly, cautiously riding through a herd of sheep.

Then we turned, and it happened.

Most mothers never know the pleasure of admiring their adult children. They tend to always slip into matriarchal overdrive, which may or may not include helicopters.

For me, because of my vulnerability, that role has changed, and I have found my hero.

The hours following my hero on the paths, roads, switchbacks and steep hills seemed particularly easy to navigate, especially since my daughter is one of the only non-medical persons who has witnessed the full onslaught of my post traumatic stress disorder. Her ability to recognize the onset of symptoms allows me to fully relax knowing she will do whatever possible to prevent the full onslaught, and that should I slip into them in spite of her preventative measures, she will be able to help me reach the other side.

After only a few hundred feet of jostling, she looked back to check and immediately stopped.

“Let me lead,” I shouted succinctly as I pedaled past, my hands gripping the handlebars tightly.

While riding 800 miles through the Rocky Mountains at altitude to train for my trip, most of the miles had been on a dirt road specifically in anticipation of this moment: mountain biking type of terrain.

The jostling spread from my head to the tips of my fingers and toes, which had gone numb except for the cold fear gripping them. Bile built in my throat, threatening to mark the trail should the oddly maniacal speed had managed to make my daughter lose sight of me.

Since I had been passive tourist, I hadn’t bothered to activate the app telling us which paths to follow, so I had no idea where we were going. I just knew that I simply could not stop until we reached the next crossroads.

I have no idea how long we bumped along, nor what our top speed reached.

I just know that I simply could not stop or we would find ourselves working through breathing exercises with a fear so deeply embedded that we would have to walk an indeterminate distance.

After what seemed to be hours of excruciating torture, I realized through the fog in my head (belying the sunny countryside through which we traversed), the jostling had ceased. I stopped, and within moments, my hero pulled up beside me.

I reached to the ground and presented her with a fresh pomegranate that lay beside my front tire.

We laughed, and as we peeled back the bright red flesh, exposing the ruby seeds resting in the yellow tissue surrounding it, she admitted, “I am glad you stopped. That was even a bit intense for me!”

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is difficult to define, difficult to diagnose since often only loved ones experience the onset, and one survivor of a specific trauma may be permanently marked while another one may walk away utterly unscathed. Alas, it is also difficult to treat. But once the mind has built an echo of the trauma, it always looms, a threat on a person’s horizon, a chimera of fear that may unexpectedly explode inside a patient’s head with the slightest provocation: a touch, a sound, a memory.

Now, whenever my daughter recognizes I am struggling with PTSD, she randomly inserts a single word into the situation.

And in the same way a hero is identified by the cape she wears, she has permanently commemorated our victory in Spain with a gorgeous tattoo featuring the luscious, propitious moment we happened to discover a wild pomegranate.

Fylgia Ear: Sant Pere Pescador

September 24, 2024

“When…one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to.”

~Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

She soared along the field, her hands outstretched, seemingly soaring above the land reminiscent of Russel Crowe in Gladiator.

I watched with mingled jealousy, admiration and pride. She was executing a move I have been unable to conquer in spite of my 1450 plus cycle touring miles and the non-touring hours I have spent in a bicycle saddle.

“It’s easy,” my brother always would prod me, even when we were children. “Always pedal at a consistent speed and keep a steady, balanced posture.”

Nope. Not easy, but then again, I have always been the type of hiker or driver that will veer toward whatever I happen to be looking toward. The view of my surrounding world has always been limited to only that which is directly in front of me.

From the outset of our journey, my daughter took the lead, setting the speed, yet always careful she didn’t ride too far in front of me, always checking to see if we could perhaps go a bit faster before she would shift into a higher gear.

She’d spent her childhood watching her father ALWAYS walk at least ten feet in front of me. “I don’t feel comfortable riding ahead of you,” she said early along our journey, something I have heard from my youngest son as well.

She didn’t need to offer an explanation for her statement. I knew why. “But the trails are not wide enough for us to ride side by side.”

”True, and I also really don’t feel like being the one to try to follow the map,” I informed her, appreciative that I no longer had to constantly be checking the small screen that had led me, often unsuccessfully, across England.

And as mother, it gave me an opportunity to take numerous photos of one of my heroes.

“I couldn’t vote for a woman. They are…”

“…too weak.”

”…too emotional.”

”…too unpredictable.”

We heard it often in 2015 and again in 2019, usually from those who have been taught that women are weaker than men, women were the cause of the fall, a woman’s place is in the home.

My mother happened to be one of the strongest women I knew. She was an orphan housed in an orphanage, abandoned by an alcoholic mother when her father served to fight in World War II. When the war ended and her father returned home, she was retrieved from the orphanage specifically so she could raise her younger brothers.

On her way home from school one day, a classmate took her into a barn and raped her. She returned home the following morning, and when she did, her father kicked her out of the house. She was fifteen.

She called a boy she had known in the orphanage, and a few months later, she was a married woman.

Little is known of her life during that time, but since her death stories have circulated of how she and her teenage husband would hop trains to travel across the country, stealing clean clothes from clotheslines, eating food they pilfered from grocery stores.

She was nineteen when she gave birth to her first child, and by the time she was pregnant with her second child (according to most stories), her husband was in jail.

She married my father, who happened to be her brother-in-law, who was father to three other children. Together, they had three more, eight combined with birth years spreading across two decades.

She filed for divorce on my sixth birthday, and worked two full time and one part time jobs to support the five children she had birthed during the seventies when the feminist movement was gaining national momentum. Yet she despised the movement. She longed to live the life of a conformist to paternal, Bible-thumping conservatives, yet her life was nothing but conventional.

But she did everything she could to perpetrate the myths of chauvinistic conformity to an ideal she never knew, a hyper-focus on paternal ideals that shaped her daughters’ perceptions, for better or for worse.

We walked through the central plaza, an exercise I force my great white wolf to do hoping eventually she will become less terrified of my favorite city this side of the pond. I ADORE Santa Fe. My fear-motivated, sometimes unwieldy service dog does not.

Every time we pass through, I inflict a miserable trip into the plaza upon us, doing what my trainers call “doggie pushups,” which entails stopping and sitting every time she becomes distraught. Our first journey across the plaza took several hours.

We are now able to cross it in half the time after more than eight very gruelling visits.

”You look as though you could use a hug,” she said as she walked toward me.

I bristled a bit, knowing that when my poor girl is so filled with fear she trembles that she is most likely to exhibit unpredictable behavior, whether that entails aggression or bolting, neither of which produce positive results.

I sat on a bench, determined to work through the scenario without her dragging me along behind as she has done in the past.

The willowy, winsome woman, sensing my apprehension, continued to approach, talking in a soothing tone and thankfully not making eye contact with my girl, eventually positioning herself on the bench with us, but maintaining a comfortable distance.

”She is wolf,” our new acquaintance observed rather than asked.

”Yes, and very difficult to manage because of her fear,” I responded while holding tightly to her harness, which serves to keep me upright as long as she is focused on her job instead of her own internal demons.

Because she had lived with intense pain in her abdomen for the first five years of her life, she isn’t intrinsically food motivated, which presents an additional challenge. She lives only to please, and when she begins exhibiting fear, she recognizes I am displeased, so often we ride on a perpetual carousel in stressful situations.

As our new acquaintance continued talking, balancing her Native American hand drum on the side of her body away from us, my girl’s trembling subsided and she actually nuzzled my hand, requesting the treat for her ability to obey the command, “Settle.”

I breathed a sigh of relief. Yes, I did need a hug, but I knew we weren’t quite there yet.

We spent an hour visiting with one another, exchanging histories, experiences, and the story spun around to my books.

“As I researched my lineage, I learned there is a remarkably long string of systemic abusers. Not just of immediate family, but the type who perpetuated violence as conquerors and aristocrats who destroyed at worst, exploited at best,” I explained. “I long to connect with my ancestors, but how am I able to do so when they were monsters?” I queried.

Then it hit, and I winced.

In many ways, I had to start with my own mother, the one who had been the first to accuse me of being so evil I was possessed. The one who had taught her daughters to submit to toxic male dominance. The one who had inflicted numerous instances of physical and emotional abuse.

I reached down, patted the warm, white head beside me, and she looked at me with what at times is an irritating devotion, convicting me because too often I am impatient with her.

The woman beside us mirrored my gesture, hugged me, and whispered one word of wisdom before rising and walking away with her drum swaying on her hip while she beat out a slow cadence rhythmically echoing her receding step: “Forgiveness.”

Sometimes keeping one’s balance isn’t about strength, but about identifying your weaknesses and moving along at a steady pace.

Haters Gonna Hate: Besalú

September 23, 2024

“I would ask you to write all kinds of books, hesitating at no subject however trivial or however vast. By hook or by crook, I hope that you will possess yourselves of money enough to travel and to idle, to contemplate the future or the past of the world, to dream over books and loiter at street corners and let the line of thought dip into the stream.”

~Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

The titillating, energetic lilt of his accordion resonated over the roar of the assaulting jets, providing a delightful cadence for the echo of Woolf and Forster alike. He was a troubadour squeezing out the unspoken tale of Besalu: the unspoken lyrics of both Jews and Catalonians who had created the lovely city stretching below our secluded balcony.

The ancient stone bridge, featuring seven uneven arches and two towers, leads straight into the Jewish quarter, which possesses the only extant Jewish ritual cleansing pool, a mikvah: a clear reflection of the importance of the Jewish presence in the area during the Medieval period and served as a figurative transition from high Latin to vernacular as birthplace to thirteenth century poet and theoretician, Raimon Vidal Bezaudun. Compare his work to that of Dante, who helped Italy officially adopt the common language of the region. Raimon noted that “all people wish to listen to troubadour songs and to compose them, including Christians, Saracens, Jews, emperors, princes, kings, dukes, counts, viscounts, vavassours, knights, clerics, townsmen, and villenins.”

Raimon Vidal Bezuandun recognized the uniting power of language, music and storytelling, important aspects of preserving culture through oral conveyance, the essence of my historical fiction in which the women who marry into my family recreate the tales of the land through which they travel as well as that of previous generations, often conveyed through stories told around a campfire or hearth, a concept reflective of Woolf’s observation that “fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly, perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners.” I weave my ancestors into history when they are often nothing more than a name in a list of English Peers, an anonymous entity contributing to my genetic makeup, an echo from the past that may or may not be part of a Jungian concept of collective consciousness that has shaped my reality, my perceptions, my memory.

Storytelling on all levels is becoming a lost art. AI threatens authors, artists, actors and musicians alike, especially since the number one song on the charts is currently AI generated.

Instagram with its 800 character limit and the suggested blog/chapter length has become symptomatic of shorter attention spans.

Dance remix with its altered tempos feed nightclubs with small snippets of crowd pleasers, abbreviating hits to seconds rather than minutes of the original compositions.

Reels provide sound bytes of lawmakers, highlights of theatrical or musical performances, compress days or months of photographic or film footage into 30 second snippets.

To ask readers to immerse themselves into my novels may or may not be as futile as asking over-tasked students to read a Shakespearean play, or even a fourteen line sonnet. But I am aware that on many, many occasions I had successfully done exactly that: encouraged my budding scholars to first dip themselves into a few lines, then find they wanted to fully immerse themselves in a world created by others that momentarily transported them outside of their own experiences, their own perceptions, their own memories, allowing them to slip into one very real form of collective consciousness; that of a troubadour singing the stories seeping through the pages of literature.

I believe it is no coincidence that the unifying power of language through storytelling that emerged from the Dark Ages gave birth to scientific discoveries and humanitarian movements of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, a strong testament to the strength of the practitioners of the liberal arts.

I emerged from the assaulting jets of the jacuzzi refreshed and ready to explore Besalu’s bridge, fortification, grotto, and church, thankful again for my daughter, my guide, and the fabulously functional rental she had procured, allowing us to get lost in the remarkable, ancient beauty and history that surrounded us.

“So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters; and whether it matters for ages or only for hours, nobody can say.”

~Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

New Generation: Besalú

September 23, 2024

“Life…is a public performance on the violin, in which you must learn the instrument as you go along.”

~E.M. Forester, Room with a View

For us on this particular day, our public performance was accompanied by an accordion.

Impressionist painters frequently depicted women of leisure elegantly garbed sitting separate from the crowd, confined on a wrought-iron railed balcony, raised on a pedestal above the hoi poloi of a bustling street.

Isolated. Protected. Objectified. Jailed.

Granted, their position at the time was innovative. They were depicted in the transitory space between public and private spaces. Previously women had been confined like a Mona Lisa, a Madonna receiving the glorious news that she had been penetrated by a god against her will, a demure wife with head bent piously over a prayer book: contained in interior spaces with only glimpses of the outside world through a small window built into a very thick wall.

Besalu is astounding. While Castellfollet overlooked the passage through the Garrotxa volcanic mountains comprising this section of the Pyrenees, Besalu was the seat of the kingdom encompassing a far-reaching medieval kingdom.

Our hotel was located at the entrance to a twelfth century bridge fortified with two high towers bearing what I assumed to be the Catalonian banner. The historian in me would have at one time immediately turned to my iPhone to Google it, but the post-TBI brain simply appreciated the beauty for what it was.

The view from our wrought-iron enclosed balcony spread magnificently below while the hum from the jets of the jacuzzi tub my daughter was enjoying, the whir not quite loud enough to drown out the strains of the buckster’s accordion. Children with balloons, dogs on leashes, couples walking hand in hand, many still wearing the Sunday best: all transporting me to a different age.

The parade of fellow cyclists with their padded pants and clicking cleats crossing the spanse brought me back to a pleasant reality that we were women in the current era, free to come and go at will, free to strain our muscles in healthy activity, free to sit above the rabble wearing skin-tight riding shorts with our wool clad stocking feet resting unceremoniously on the chair in front of me, a relaxed, informal sprawl scorned by Henry James in the opening lines of his novel, The American.

My reverie was interrupted by my daughter, wrapped in a towel, warning me that the jacuzzi jets were strong enough to “assault one in places that normally shouldn’t be assaulted,” a phrase that may or may not have bespoke her approval of the experience.

I turned from my accordion player with a measure of reluctance and recounted Virginia Woolf’s words: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” from the essay read repeatedly in college courses emphasizing femmism, the same one that reminds readers that “The history of men’s opposition to women’s emancipation is more interesting perhaps than the story of that emancipation itself.”

Our own Room with a View.

As I lowered my body into the steaming hot “assaulting” jets, I relished how our journey across Europe would shape my voice, my fiction, and my emancipation from restrictive mores.

”Anything may happen when womanhood has ceased to be a protected occupation.”

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Photograph: Sant Ferriol

September 21, 2024

”There is no perception which is not full of memories. With the immediate and present data of our senses we mingle a thousand details out of our past experience. In most cases, these memories supplant our actual perceptions.”

~Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

Layering is how learning happens. New perceptions mingle with old experiences, becoming embedded more thoroughly in our brain.

We sat out on the second day of our journey warm, well rested, refreshed: I was acutely aware of the sharp contrast between my frugal journeys and my daughter’s well curated, expensive tour.

The 36 miles we had traversed the previous day had been flawlessly easy compared with those I had traveled with Matilda, and in spite of the 31 miles with the altitude gain we were facing as we ascended deeper into the Pyrenees seemed inconsequential by comparison.

A trip to Europe wouldn’t be complete without a glimpse of a fortress sitting high upon a crag.

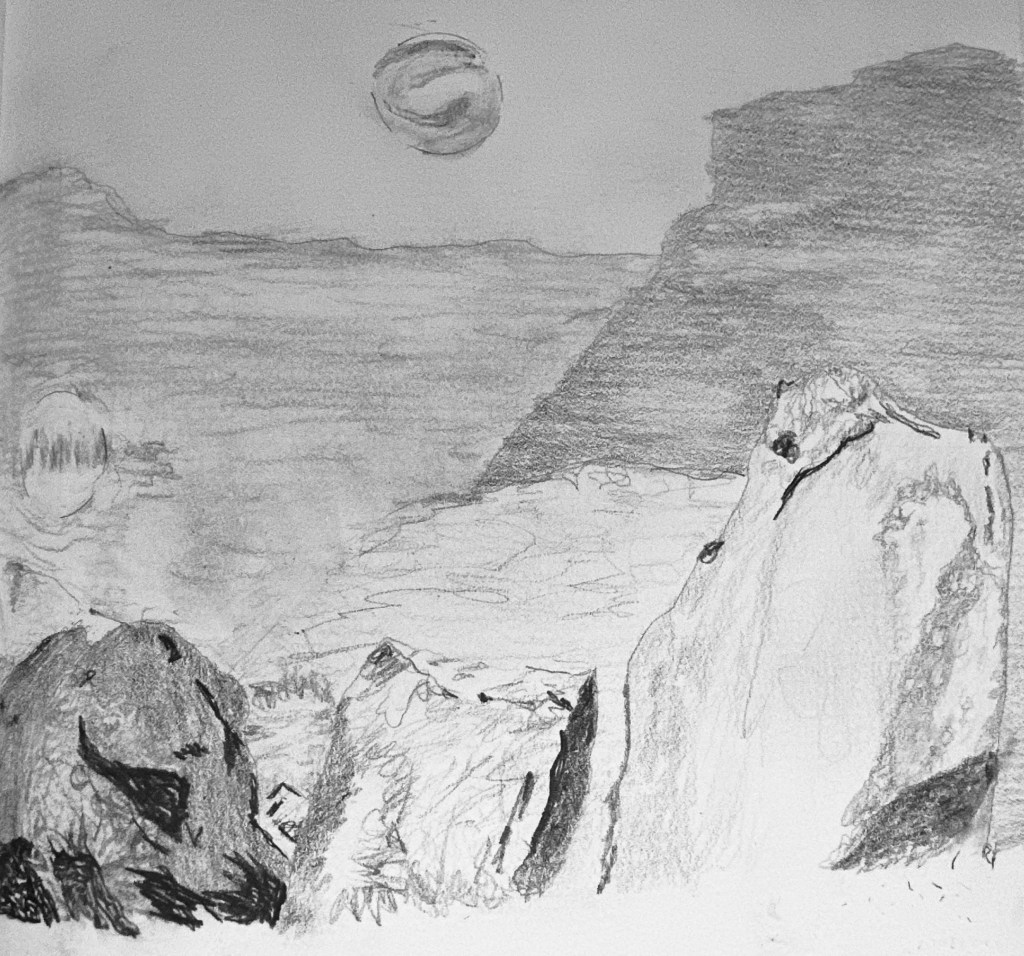

As we wound up the infrequently traveled mountain road with steep cutbacks, the clouds that had marked our previous day’s journey dispersed, yet wrapped the valleys spreading below us in gloriously picturesque horizons befitting a Romantic landscape canvas.

We stopped at what was the highest altitude of our ride through the Pyrenees, not from fatigue but because of the sheer awe-inspiring view. Both of us were grateful we were accustomed to the thin air of the Colorado Rockies. The ascent had seemed paltry for me, especially because the two weeks of wrestling Matilda following my intense 800 mile training at over 8000 foot altitude. The mere 2,850 foot elevation was nearly laughable since the app warned us the ascent may be difficult.

Yet we remained breathless.

She walked ahead with her camera, a sight that had brought me pleasure since she had first aspired to become a photojournalist in high school, a goal that had placed her on college and professional athletic sidelines, a study-abroad program in Indonesia, and in a number of lucrative scholarships. She has long since stepped beyond that goal, but her eye for photography remains firmly intact.

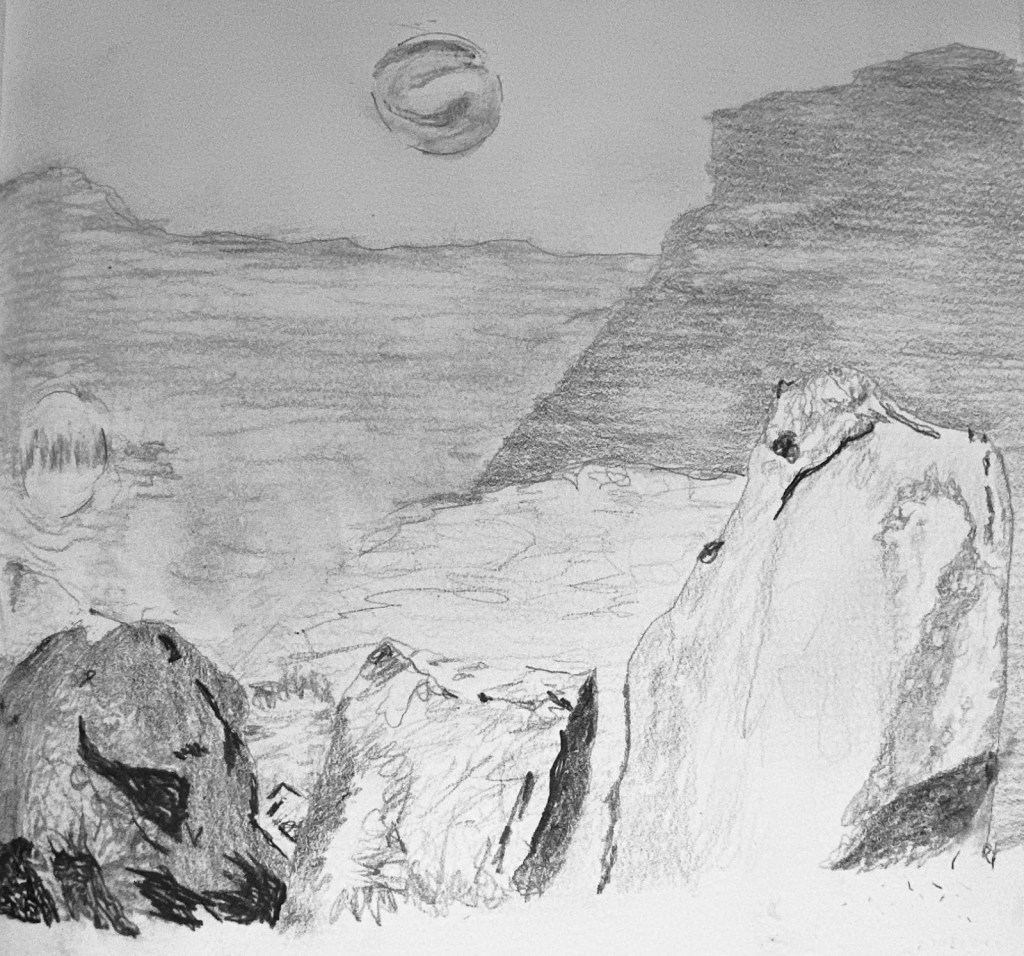

She stood overlooking the vista in much the same way as Friedrich’s Wanderer on the Sea of Fog: a solitary figure contemplating the mysterious beauty spreading below.

As we soared downhill after an hour of contemplative repose, our speed was nearly as exhilarating as the view we had just absorbed.

But only nearly.

The intoxicating beauty and heady descent surpassed any Romantic Era canvas I have ever admired and will remain forever firmly embedded in my memory.

Half way down toward our next destination, it appeared on the horizon, and it did not disappoint. An entire medieval city sat atop a volcanic formation. The “Castle of the Rock”: Castellfollet de la Roca.

“That is one of the stops they recommend for lunch,” she said as we shot the obligatory photos from afar, ones she had disdained because we were too far to get a clear shot.

“We have two choices. Continue relatively downhill to our next destination, which is only about 45 minutes away, or climb that extraordinarily steep hill. I am willing to do either,” she said with a tone belying her words. I am, after all, her mother and had heard it many, many times.

I looked longingly left toward the perched edifice, then right down the road we could take. Without a word, I climbed onto the bike saddle and began pedaling up the steep hill, fearing the worst, which would have entailed us walking our E-bikes half way up, delighted when we reached the top without a hiccup, a wonderful contrast to my experiences with Matilda!

The view wasn’t much from within the only small, family-owned restaurant we found open during midday Sunday siesta (which is NOT a myth in Catalonia). Well, unless the “view” included momentary glimpses of the swarthy, smiling, dancing young man wielding his magical implements over the massive brick oven.

The wizard’s sumptuous fare offered to us was sheer ambrosia from start to finish.

Perfectly apropos for our day among the clouds.

Whipped Cream: Olot

September 21, 2024

“My body…to exercise on other images a real influence, and, consequently, [is] to decide which step to take among several which are all materially possible…. Surrounding images…must display…the profit from which my body can gain from them…. I note that the size, shape, even the colour, of external objects is modified according as my body approaches or recedes from them; that the strength of an odour, the intensity of a sound, increases or diminishes with distance…. My horizon widens, the images which surround me seem to be painted upon a more uniform background and become to me more indifferent.

~Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

We are sentient human beings, interpreting our world through our senses, recording snippets of information from our myriad of experiences, creating memories that may be flawed by our limited perception.

Travel broadens one’s horizon. Tastes, smells, textures, temperatures, images and sounds bombard us, yet not all become permanent records of any particular instant.

Bergson rightfully quantifies memories extracted from the images which bombard us in monetary terms: they are “profit.”

“If you ever travel to Europe,” my first humanities instructor told her students, “treat yourself to a cup of hot chocolate,” she informed us as we read the opening pages of Anna Karenina. She was illustrating the discrepancy from our own limited perception of indulgence, privilege and wealth as students occupying one of the poorest counties in America from the reality of Russian aristocrats in the novel.

Having been assured even by the English I had met across the countryside that the second leg of my journey through Spain would be fabulously warm compared with the freezing sleet I had unexpectedly encountered there, I had left most of my warm layers beside a trash bin in London.

Our first day in Spain had seen rain so torrential it filled the gutters and spilled onto sidewalks and shops. Our first day of our bicycle ride had found us splattered in mud that dripped down our helmets, jackets and backsides like brown streaks of sewage.

By the time we reached our first destination, we were shivering, dirty, cold. But the physical exertion of riding through the astounding beauty of the Pyrenees buoyed us, energized us, enlivened us. After washing away the grit, we were ready to explore Olot. Since I had left behind all my cold weather gear when I left London, I wrapped the bed runner around me like an oversized scarf and headed into the heart of a city that dates back to the seventh century.

The rain continued to fall, and warm shops glowing in the night beckoned to us. Famished, we stepped into a quaint, sumptuous pastelería, compelled by its array of delicate, decadent cakes and candies artfully displayed in ancient cabinetry as dark as the chocolate delectables.

You know how you should never step into a grocery store hungry? That applies to confectioneries twofold, and the counter began filling with our selected indulgences: fudge, cookies, sweetbreads. And as we began to pay, the sign touted the very object of desire my memories had long since shelved: the experience of European hot chocolate.

We sat on the cold stoop of a closed tourist trap spooning out generous portions of sweetness and listened to the peals of the eleventh century cathedral. The illuminated, freshly rain-baptized streets of Olot’s Nucli antic seemed to be a small corner of heaven.

Memories derived from our senses: sights, sounds, scents, textures and tastes from which our souls deeply will forever profit.

My Dog: Garrotxa Volcanic Zone

September 21, 2024

I carry her wherever I go.

Losing a fuzzy is the deepest pain I have ever experienced, and when my old girl, my sweet Great Pyrenees who had accompanied me on my 825 mile bicycle ride from Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive to the border of Colorado in 2013 could no longer stand, a quick progression from walking miles along the Boulder Creek Path in a matter of days, I knew it was time.

She had helped me earn my master’s degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, walking hundreds of miles alongside me, waiting patiently while I took photographs, shot video, recorded interviews with passers-by.

She had helped me learn to walk again after sustaining my traumatic brain injury.

As we walked out of the vet, my daughter said for a moment she had feared I had gone with her.

She was my heart, my soul.

Before laying beside her on the floor of the room designed specifically for euthanization, I took off her harness because like me, she loved her freedom. She loved independence. She loved being stubborn, so much so that if she didn’t want to go a particular direction while we were walking, she would obstinately throw her 86 pounds onto the sidewalk and would refuse to budge unless I complied with her demand.

I wrapped my arm across her warm body, knowing within minutes it would turn cold, closed my eyes so I wouldn’t see the needle they would soon insert into her body, and literally couldn’t breathe.

The ordeal had been slow and awkward; she was stubborn even then, resisting the flow of the infusion, her heart beating even though all the solution in the bag had passed into her body.

My daughter described the horrifying process: her blood had flown back into the tube of the port while the veterinarian left the room to retrieve an additional bag of solution, details to which I had remained oblivious because I had been unable to do anything other than hold her warm body against mine as I spooned her.

She was larger than I was in many ways: her hips would rise above mine when we laid side by side, and if she stretched out fully, her feet would extend beyond mine. In every way, we “fit” together.

The vet left the room long before I was able to pull my arm off her cold body. I truly didn’t want to leave without her, the same way, I would later learn, she seemed to resist leaving without me.

When I retrieved her ashes a few days later, I was astounded by the weight of the box, and I know now that our ashes probably will be similar quantities.

My novels open with the moment when she and I are reunited as our ashes are tossed into a smouldering fire in a grove of aspen along the same wilderness where I once hiked with my infant children strapped to my back, the same location where I have known since those hikes where I want my ashes to be scattered.

When I set out on my journey across Europe, I wore three things around my neck: my sunflower lanyard identifying me as disabled, my “do not resuscitate” designation which clanged against her tags, and a small silver tree with a blue crystal in the center securing a few of her ashes.

It seemed appropriate that at least part of her would make my second epic cycling journey with me.

We were nearly finished with our first day of riding through the Great Pyrenees when we stopped at the delightful cafe located in Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park. Before hopping back onto the E-bike saddle, I made one last trip into the cafe to use the facilities, and that’s when I noticed the pendant was gone: somewhere along the way as we rode through the Pyrenees, she must have preferred a path we hadn’t taken and she had obstinately thrown the bit of her I had carried with me onto the ground.

Initially I grew as cold as I had on our last day together, but as she always did in her moments of infuriating obstinance, she elicited the indulgent laugh only a mother would find when embracing a child’s endearing flaw.

Still dizzy in spite of the humor, I shared the moment with my daughter, who also chuckled as we mounted our mud-covered bikes for the last push for the day along our designated trail.

Pigs: Olot

September 21, 2024

Both curses and blessings require a name be spoken.

In many cultures, names are given long after an infant is born and must reflect the nature of the child or the times in which they live, and naming day is a holy moment for babe and observers alike.

As we set off, and throughout the entire journey, the E-bikes we had rented remained nameless.

They happened to be so very perfect, no curses were necessary. And well, as far as blessings, some would actually have used the phrase, “We were so blessed” to have such a perfect pair.

“Oh, the weather you’ll encounter will be so much warmer. And drier,” my new friend from England had laughed when she learned the second half of my Eroupean E-bike tour would be in Spain.

”This is perfect,” my daughter shouted toward me as she led us along the gravel road. It was, indeed, a splendid start for our 425 mile route. But not for long.

Although our cycles were perfect, the weather wasn’t.

As the mist began falling, we were still in high spirits.

Instead of taking almost a week to learn the gears and settings, it had taken us only a few minutes. Our E-bikes were light and well balanced, and within just a few miles we began averaging speeds I had only achieved going downhill with an out of control, brakeless Matilda.

The mountain range through which we would ride the next few days rose above the clouds like an awaiting nirvana as we rode from one picturesque village with bright red tiled roofs to another.

When we had at last hit the blanket of heavy clouds that had painted a picturesque landscape in the distance, we stopped for lunch.

Catalina is an odd cross between Spanish, French and Italian. And utterly foreign to either of us, but when the server brought out two plates of pig’s feet, we knew the universal head shake: “No, that’s not what we ordered.”

Food after a long ride always tastes marvelous, and our abundant serving of pure protein consisting of pork chops, eggs, and any other number of fantastic but unidentifiable meats buoyed us for what was to come: the Spanish Pyrenees.

Our repast may have kept us afloat, but it didn’t keep us dry after only a few minutes of relentless rain.

“The rain falls only on the plains in Spain,” a jumbled quote from one of the most despicably misogynistic films I’ve watched kept flooding my brain.

By the time we arrived at what the fancy app my daughter had downloaded from our bicycle rental shop had identified as a quaint, pleasant coffee shop where the proprietor speaks English, we were coated in Spanish mud from helmet to tire to toe.

We quickly ordered and stepped out of the pristinely clean establishment, finding a secluded spot on the patio nestled in a series of fern-covered extinct volcanoes while American pop played quietly in the background.

This time when the server brought us our midday steaming hot, black espresso, we didn’t have to waive aside an order of unwanted pig’s feet with our frightfully mud-blackened riding gloves.

Ships and Shame: Girona Cathedral

September 20, 2025

“Neither knows where the other goes or lives. We might have loved, and you knew this might be.”

~Baudelaire

My daughter and I rushed from one site to the next, following a map she had discovered on any number of apps she has running at any given time, those magical things throughout my journey around England I dare not delve into because I had no concept of data usage limits, wary even of trying to log into the WiFi at each location, fearing that I would encounter the same type of hidden fees I did while availing myself of a shower.

The Jewish Grotto. The museum dedicated to Medieval Architecture. The Roman Wall. The Cathedral. The shopping district. The Bridges.

Tourists are different from transients. They go in pairs or groups. They have purpose. They have plans.

But because they are isolated entities specifically intent upon consuming as much of the geographical area in which they travel, they never fully immerse in their surroundings and rarely have meaningful encounters with those they meet.

He knelt before me with one knee resting on the cool, green grass.

I sat upon one of my very low-slung camp chairs beside my wolf-dog with her ears pinned tightly against her head, the only indicator to an observant passerby that they were not observing a sweetly romantic proposal.

The perfect photo opportunity a street photographer would feel compelled to snap then later reveal to the couple that he possessed the capture of the moment and would kindly share it as a “gift” to the happy couple in exchange for a follow on social media.

His guitar sat in its case beside him, and if one were a careful observer, they would understand he wasn’t searching the ground for a dropped diamond, but instead was struggling to find the green pick he feared he had dropped in the grass.

No proposal. No romance. Nothing more than just a strummed song that had enough minor bridges it echoed slightly of Jimmy Page.

“Try stepping away from your writing,” she suggested, which was deeply ironic given the fact that she and I had earned our degree in English Lit together.

I’d explained I had hit a wall with both my novel and my memoirs. My thoughts would race endlessly throughout the night, but as soon as I would open my iPad, nothing.

“Yeah. Right,” I scoffed in return.

”No, don’t step away from writing, step away from your current projects. Here, I’ll send you a link that offers writing prompts,” she added.

Dutifully, I opened the links and began perusing a few of the suggestions, which, ironically, corresponded very specifically with any number of scenarios I have outlined in my eight novels. And if the prompts didn’t correspond with my novels, they corresponded with my memoirs.

I thanked her kindly for her suggestion, pointed out the conundrum, and began writing my memoirs and novels again.

Our conversations, though at times years pass without communicating at all, are always lively if not slightly heated at times.

She and I shared only one actual class together: French. Yet we ended up reading the same material on many occasions. Although I was pursuing a slightly different program for my second degree, Humanities, she was pursuing one in Fine Arts. Sometimes the same animal, but from a slightly different perspective. One is hands on art making with a sprinkling of theory, the other is theory with a sprinkling of art making.

I prefer theory.

It is clinical, cynical, critical. Perfectly ME.

That’s what I love about my transient lifestyle. Any time I introduce myself to others who share #vanlife, a simple “Rj” will suffice when, after an interlude lasting anywhere from fifteen minutes to five hours, we finally exchange names. We are transient enough to understand that whatever nickname we have adopted for either a day, a decade, or an eternity for the moment embodies everything about our personhood. For a moment, we connect, knowing that we must embrace the spontaneity, the passion, the connection we encounter because we will be highly unlikely to ever see one another again. And our professions change as quickly as our nicknames.

The Artist. The Author. The Botanist. The Philosopher. The Priestess. The Magician. The Musician.

The Butcher. The Baker. The Candlestick Maker.

And yes, given our current statuses, like those in the nursery rhyme, we are all knaves according to the voting majority in need of “involuntary lethal injections.”

No wonder we shift in and out of identities and professions as quickly as we do locations. And no wonder our art, our philosophy, our religion, our ethos is feared.

Grotesquery.

But we are rudimentary parts of society possessing the powerful freedom they long to suppress.

“The delight of a city-dweller is not so much love at first sight as love at last sight,” Benjamin observed regarding Baudelaire’s perception of the flâneur. The commonality was the concept of love viewed not as a moment rife with possibility and promise, but of opportunities acknowledged yet never pursued any further than a glance. The type of romance that opens Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast in which he spies a woman at the bar and without ever talking to her declares her to be his.

They pass one another in the night, like ships or airplanes; each only slightly aware of one another’s presence, a mere blip on a very overcrowded radar. The happenstance mutual encounter never acted upon but with a visceral spark recognized by both parties.

The only successful romance I may ever know is that of a flâneuse: one comprised of distantly alluring fantasy. Not hands on, but existing only in theoretical contexts. One that perfectly suits me as I continue dwelling in a series of deserts, towns and cities alike; always a cognizant, nonchalant, observant detective searching for the next story, the next memoir, the next unspoken dialogue waiting to be recorded in words upon the blank pages of my journals.

But my disconnected transience is a lifestyle with which I am deeply in love.

Runnin’ Outta Fools: Girona

September 20, 2025

”To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you

something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

~Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Who are you?” the Faceless One insisted in The Game of Thrones.

”I am no one,” Arya replied, longing to belong.

After being attacked in a brutal assault staged ironically in Girona’s Jewish Quarter by the one who had been tasked to serve as her mentor throughout the process of learning to assume identities of the dead, Arya boldly declares her own personhood, citing her royal heritage alongside her own accomplishments.

She has become.

Every time I enter the vast stone recesses of what had once been sacred ground, I feel the tinge of regret that I senselessly allowed to be distracted from the tuggings of my heart when I felt compelled to take on the cloth, but as I sit writing with nothing but the sound of grasshoppers flying lazily, fighting against the overnight cold that will soon end their lives, I know I am, in many ways, living as much of a quiet sequestered life now as I would have if I had followed what I had perceived to be my calling.

But the longing remains.

“Perhaps the solitude of your current life is where you were meant to be,” she stated on the Desert Monastery page I follow.

Purpose and destiny. I’ve struggled with that most of my life, stubbornly believing there is “The One” out there for everyone, yet coming to peace with the possibility that is not the case for me.

“You are far too independent to ever be in a relationship.” I have heard that criticism almost as often as I have been accused of being evil. Perhaps to many, for a woman they are synonymous.

“Know thyself,” the threshold at Delphi instructs.

For a time, a short season, I did. No significant other, a career I loved, a future of which I had been utterly, overly confident.

And then I met with an hydraulic lift on a hot July afternoon.

The majority of Americans, it is said, are only one accident or illness away from homelessness. I am among those statistics.

After my injury as I began to emerge from the drug-induced haze, even before I became aware that I had lost my ability to read, I understood that my dependence was as ephemeral as my future. Both were lost at once. And my daughter had to step into the role of caregiver even before she had the chance to be married, to develop her own destiny.

“To Thine Own Self Be True.”

”She just isn’t pretty enough.”

“She is too fat.”

”She’s too smart for her own good.”

”She dresses like a whore.”

”She is such a slut.”

”She is insatiable.”

They are the external voices a girl begins hearing even before she is able to speak herself.

The phrase, ”Oh, she is so beautiful,” is often uttered in a nursery.

Right alongside, “She’s such a chunk.”

And when she reaches for her first toy, “She’s so smart!”

Quickly a toddler is instructed, “Sit with your knees together when you are wearing a dress.”

”Keep that dime between your legs,” she is told as she approaches puberty.

”Women aren’t as sexualized as men,” we hear even from pop psychologists.

With so many societal perceptions hurled at a young girl, who ever has the opportunity to know oneself, much less be true?

Are we predestined to a particular fate, or should we, as Arya had done after battling her foe in Girona’s Jewish Quarter, be free to declare our own destiny?

As I followed my guide from one destination to the next in the waning light of Girona, for now I was relieved and thrilled to have a daughter confident enough to wander for miles in a town she had never visited, showing me marvelous bits of history and culture I would have never known without her help.

Independent, informed, decisive, knowledgeable, and strong. I couldn’t be any more proud of her and who she has become.

Start the Fire: Girona

September 20, 2025

We were the only occupants in the monastery, our footsteps echoing through the vast recesses of the nave, a reminder that the incredible edifices scattered everywhere across Europe were designed with two purposes: reverence and acoustics. Like many of its sister buildings, this one had been repurposed into a museum. We walked from exhibit to exhibit, and I absorbed absolutely nothing but the wonder of the architecture, which had at one point recently been filled with the accoutrements of Hollywood rather than the quiet whispers of the devout for whom it had originally been erected.

Girona had been revitalized by the influx of producers, cinematographers, goffs and actors. Even the Roman Wall now stretching for miles through the small town, a crumbling edifice before the Game of Thrones filming crews arrived, has been rebuilt, the safety features carefully, intricately hidden beneath the new but perfectly aged stonework. Everything had been touched, altered.

Walter Benjamin maintains that mechanical reproduction, whether through photography or film, separates art objects from its original ritualistic essence, yet the connotation remains. A head bowed in art whether from shame or prayer will always connote a measure of piety, whether it be represented in film as a momentary gesture of a villain plotting evil and looking at his hands as he cracks a lock on a safe or loads a cartridge into a gun, thereby alluding to his inherent guilt regarding his evil nature, or a venerated saint depicted on a wooden panel looking at a prayer book held in her lap.

Likewise, the lofty ceilings of the old abbey in Gerona converted into a museum, when depicted in Game of Thrones, became the backdrop for the god-like faceless man of Westeros. Yes, those same lofty pointed arches, originally designed by Romans for their basilicas where legislation and commerce was enacted with the approval of the god-descended Cæsars, eventually had been assimilated during the eleventh century by European kings who believed themselves to be appointed by God. And yes, the same architecture had eventually been adopted by universities, but only during the Renaissance as secular humanistic philosophy began rising to challenge concepts of sacred.

The same lofty design, always associated with god-like proceedings.

As Benjamin noted, reproduction of art through the mechanical lens of photography and film has taken the objects out of the hands of the church, but the separation of object from its original ritualistic aura may never be fully achieved. Society is perhaps too conditioned by centuries of tradition to ever fully change.

Likewise, racial, cultural and socioeconomic profiling, though never acceptable, has always been a prominent part of human civilization.

When Benjamin fled Germany, both he and his work were relatively unknown. Sure, he had successfully published a few critical articles in journals primarily consumed by academics who arguably have always been a bit too intent upon studying their own navels or the navels of equally erudite white men. He had even become a frequent lecturer and debater at the German Youth Movement meetings. He earned his doctorate and longed for a career in academia, but he didn’t have the financial means to do so; he had a short stint as an instructor at the University of Heidelberg, but his dream would never be fully realized in his lifetime, though his works now appear in numerous college and university syllabuses.

Benjamin, understanding the political turmoil mounting in Germany, fled to France, where in 1936 he penned “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” a treatise recognizing the inherent political nature of art, arguing that mechanical reproduction would save art from being a useful tool in the hands of fascist regimes. As Jew, he would have been among those forced to don the six-pointed star when the fascists began separating and identifying different groups once the Nuremberg Laws were ratified on September 15, 1935.

Throughout European history, Jews were often confined to specific neighborhoods, whether through choice or legislation. They worshipped differently. They spoke differently. They conducted commerce differently. And the basic precept of Sabbath with its inherent laws regarding labor and worship encouraged isolation since they were allowed a limited number of steps one day of each week, so living near the tabernacles was highly practical, an isolationist lifestyle that made the onset of the Holocaust far too easy.

And because of their differences, they were despised.

During the late fifteenth century, Jews of the Spanish diaspora had been forced by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella to take on the mantle of Christianity, forcing them to practice their traditions in secret.